Fears about China's influence are a rerun of attitudes to Japan 80 years ago

- Written by Honae Cuffe, PhD Candidate, History, University of Newcastle

July 1 marked the 80th anniversary of Australia’s iron ore embargo against Japan. The official reason[1] was resource conservation, but the ban was really driven by a fear of Japan – which had been buying up assets like iron ore and scrap metal – gaining a stronghold in Australia that threatened our sovereignty and security.

Despite the passing of 80 years, Australia is having the same discussions we had back in 1938, only this time about China.

China’s growing commercial influence in Australia and other Asia-Pacific countries has sparked concerns about its political ambitions. Responding to these concerns with economic sanctions is likely only to pander to US desires to curb Chinese influence, placing Australia’s economic future and regional security at risk.

The economic sanctions Japan faced[2] in the 1930s and early 1940s contributed in large part to the outbreak of the Pacific War.

With the recent tit-for-tat US and Chinese trade restrictions[3], is the world heading down a similar path?

What can we do differently this time around?

Australia must recast its foreign policy with a view to the role it wishes to play in its immediate region. This needs to be a little more adventurous than the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper[4].

The Australia of the 1930s faced a region in flux. There were territorial disputes, the waning power of Britain – Australia’s primary ally and protector – and the growing military and commercial weight of regional power Japan, whose intentions remained unclear. Sound familiar?

In early 1937, fears emerged of a world steel shortage. While iron ore restrictions were being introduced elsewhere, the Australian government maintained[5] that it was not a lack of resources that had created a shortage but an inadequate output.

It came as quite a surprise then, in May 1938, when the Australian government announced an embargo on iron ore exports, effective July 1 1938. The government cited a (then) recent and very brief report[6], compiled by the Commonwealth government geological adviser, which concluded iron ore deposits were much smaller than had been estimated and perhaps would not meet domestic needs.

Read more: Australia is hedging its bets on China with the latest Foreign Policy White Paper[7]

The embargo included existing agreements with foreign investors, such as the Japanese lease at the Yampi Sound[8] mines in Western Australia, where preparations for the first iron ore extraction were well under way.

The government stressed that the embargo was not due to anti-Japanese sentiment. Nevertheless, this was the conclusion the Japanese government drew as it tried and failed to secure access to the Yampi Sound project.

The size of Australia’s current iron ore exports calls into question the logic of this report and the export ban it led to.

A foreign foothold in Australian territory

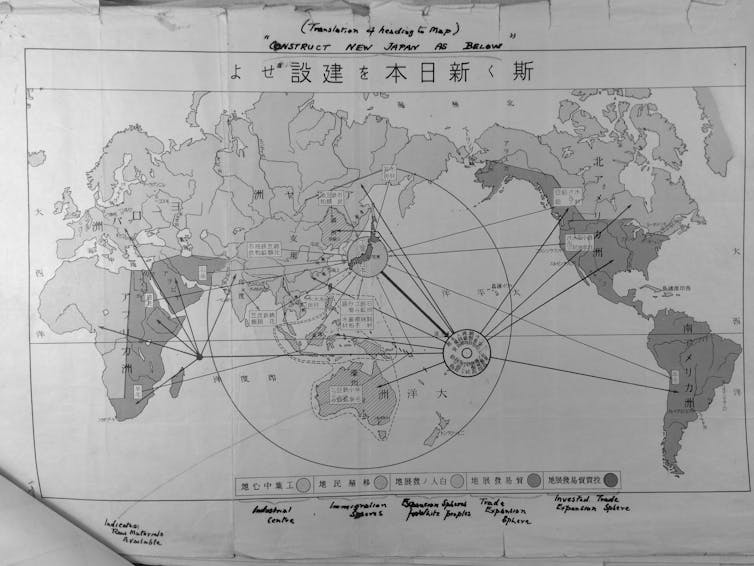

Throughout the 1930s, Japan pursued a policy of southward expansion[9], both territorial and economic in nature. At the centre of this policy was the need for resources to cater for Japan’s rapidly growing population. This involved the “economic penetration” of Far Eastern nations, investing Japanese capital to secure essential goods.

Australia, still recovering from the Great Depression, welcomed these investments.

‘Construct new Japan as Below’. Legend reads: Industrial Centre, Immigration Spheres, Expansion Spheres for White Races, Trade Expansion Spheres, Investment Expansion Spheres.

From the Collection of the National Archives of Australia, A601, 402/17/30.

‘Construct new Japan as Below’. Legend reads: Industrial Centre, Immigration Spheres, Expansion Spheres for White Races, Trade Expansion Spheres, Investment Expansion Spheres.

From the Collection of the National Archives of Australia, A601, 402/17/30.

Japan’s visions for territorial expansions became clear in July 1937. Japan – as Australia had long feared[10] – proved itself an aggressor when its army invaded China, signalling the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Australia opted for a diplomatic response to this conflict, remaining impartial and encouraging “cooperation and conciliation[11]” as the solution.

However, Japanese economic investments were being viewed with increasing caution.

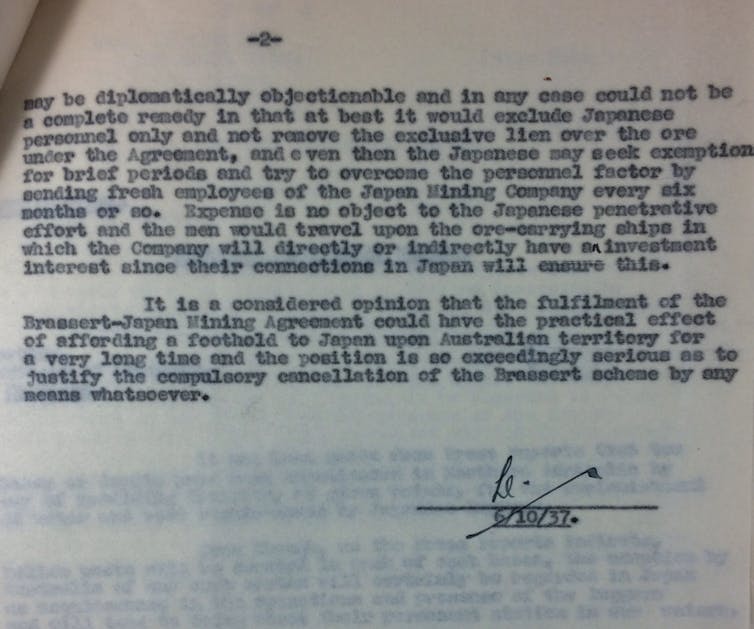

Australia’s trade commissioner in Tokyo, Eric E. Longfield Lloyd, reported that Japan’s territorial expansion into China had been aided by a seemingly innocent system of economic penetration throughout the 1920s and ’30s. He feared that allowing the Yampi Sound project to continue, operated as it was by Japanese staff, would result in a “foreign foothold” in Australian territory.

From the collections of the National Archives of Australia, A601, 402/17/30.

Longfield Lloyd pressed for the project’s cancellation “by any means whatsoever”. One proposal was was an export embargo “by declaration of insufficiency”.

Here was the origin of the 1938 iron ore embargo.

Chequebook diplomacy

Much like in 1938, today’s fears about Chinese investments hinge on the question of political influence and security implications.

These concern have led to the limiting of property investments[12] and the banning of foreign political donations[13].

Further afield, China’s vast infrastructure program, the Belt and Road Initiative[14], has sparked speculation that the nation is using chequebook diplomacy – and perhaps debt-book diplomacy[15] – to secure economic leverage and gain greater influence in regional and global affairs.

This is of particular concern in Australia’s immediate sphere of influence, Southeast Asia and the South Pacific.

Most recently, the Australian government sought to protect its diplomatic and security interests when it outbid the Chinese telecom giant Huawei[16] for the rights to construct a network of internet cables linking the Solomon Islands to Sydney.

Time for a long-range view of Australia and its foreign policy

The economic pressure exerted on Japan in the 1930s and early 1940s – in which Australia was by no means alone, with the US and Britain leading the charge – deprived the nation of its means of survival. This hastened the campaign of aggressive regional conquest in pursuit of raw materials that eventually led to Pacific War.

To be sure, China’s current economic position makes it unlikely that trade sanctions will lead to armed conflict. But throw in territorial disputes[17], erratic leadership, the US-China struggle for Pacific dominance, and the future seems a lot less certain.

With all this in mind, the 1938 iron ore embargo does serve as a warning against over-reliance and a blinkered outlook that sees only potential dangers in our immediate region.

Now is the time for Australian to broaden its foreign relations, avoiding the potential downfall of over-reliance on the Chinese market and the US alliance, while building new diplomatic ties.

There is such an opportunity in Australia’s neighbourhood, “that part of the world”, as shadow defence minister Richard Marles recently argued[18], “in which our influence matters the greatest. What we say and do in the Pacific carries enormous weight.”

Australia must take the initiative in its immediate region to develop varied and mutually beneficial economic, diplomatic and strategic relationships.

In this way, Australia can strengthen its own economy, the economies nearby and its role as a regional leader and collaborator.

From the collections of the National Archives of Australia, A601, 402/17/30.

Longfield Lloyd pressed for the project’s cancellation “by any means whatsoever”. One proposal was was an export embargo “by declaration of insufficiency”.

Here was the origin of the 1938 iron ore embargo.

Chequebook diplomacy

Much like in 1938, today’s fears about Chinese investments hinge on the question of political influence and security implications.

These concern have led to the limiting of property investments[12] and the banning of foreign political donations[13].

Further afield, China’s vast infrastructure program, the Belt and Road Initiative[14], has sparked speculation that the nation is using chequebook diplomacy – and perhaps debt-book diplomacy[15] – to secure economic leverage and gain greater influence in regional and global affairs.

This is of particular concern in Australia’s immediate sphere of influence, Southeast Asia and the South Pacific.

Most recently, the Australian government sought to protect its diplomatic and security interests when it outbid the Chinese telecom giant Huawei[16] for the rights to construct a network of internet cables linking the Solomon Islands to Sydney.

Time for a long-range view of Australia and its foreign policy

The economic pressure exerted on Japan in the 1930s and early 1940s – in which Australia was by no means alone, with the US and Britain leading the charge – deprived the nation of its means of survival. This hastened the campaign of aggressive regional conquest in pursuit of raw materials that eventually led to Pacific War.

To be sure, China’s current economic position makes it unlikely that trade sanctions will lead to armed conflict. But throw in territorial disputes[17], erratic leadership, the US-China struggle for Pacific dominance, and the future seems a lot less certain.

With all this in mind, the 1938 iron ore embargo does serve as a warning against over-reliance and a blinkered outlook that sees only potential dangers in our immediate region.

Now is the time for Australian to broaden its foreign relations, avoiding the potential downfall of over-reliance on the Chinese market and the US alliance, while building new diplomatic ties.

There is such an opportunity in Australia’s neighbourhood, “that part of the world”, as shadow defence minister Richard Marles recently argued[18], “in which our influence matters the greatest. What we say and do in the Pacific carries enormous weight.”

Australia must take the initiative in its immediate region to develop varied and mutually beneficial economic, diplomatic and strategic relationships.

In this way, Australia can strengthen its own economy, the economies nearby and its role as a regional leader and collaborator.

References

- ^ official reason (www.nma.gov.au)

- ^ economic sanctions Japan faced (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ tit-for-tat US and Chinese trade restrictions (theconversation.com)

- ^ 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper (www.fpwhitepaper.gov.au)

- ^ Australian government maintained (trove.nla.gov.au)

- ^ brief report (trove.nla.gov.au)

- ^ Australia is hedging its bets on China with the latest Foreign Policy White Paper (theconversation.com)

- ^ Japanese lease at the Yampi Sound (trove.nla.gov.au)

- ^ policy of southward expansion (www.bbc.co.uk)

- ^ as Australia had long feared (www.awm.gov.au)

- ^ cooperation and conciliation (electionspeeches.moadoph.gov.au)

- ^ limiting of property investments (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ banning of foreign political donations (www.reuters.com)

- ^ Belt and Road Initiative (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ debt-book diplomacy (theconversation.com)

- ^ outbid the Chinese telecom giant Huawei (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ territorial disputes (theconversation.com)

- ^ recently argued (www.lowyinstitute.org)

Authors: Honae Cuffe, PhD Candidate, History, University of Newcastle