The death of the open-plan office? Not quite, but a revolution is in the air

- Written by Andrew Wallace, Program director of Interior Architecture, University of South Australia

“What will it take to encourage much more widespread reliance on working at home for at least part of each week?” asked Frank Schiff, the chief economist of the US Committee for Economic Development, in The Washington Post[1] in 1979.

Four decades on, we have the answer.

But COVID-19 doesn’t spell the end of the centralised office predicted by futurists since at least the 1970s.

The organisational benefits of the “propinquity effect” – the tendency to develop deeper relationships with those we see most regularly – are well-established.

The open-plan office will have to evolve, though, finding its true purpose as a collaborative work space augmented by remote work.

If we’re smart about it, necessity might turn out to be the mother of reinvention, giving us the best of both centralised and decentralised, collaborative and private working worlds.

Cultural resistance

Organisational culture, not technology, has long been the key force keeping us in central offices.

“That was the case in 1974 and is still the case today,” observed the “father of telecommuting” Jack Nilles in 2015[2], three decades after he and his University of Southern California colleagues published their landmark report Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff: Options for Tomorrow[3]. “The adoption of telework is still well behind its potential.”

Read more: 50 years of bold predictions about remote work: it isn't all about technology[4]

Until now.

But it has taken a pandemic to change the status quo – evidence enough of culture resistance.

In his 1979 article, Schiff outlined three key objections to working from home:

how to tell how well workers are doing, or if they are working at all

employees’ need for contact with coworkers and others

too many distractions.

To the first objection, Schiff responded that experts agreed performance is best judged by output and the organisation’s objectives. To the third, he noted: “In many cases, the opposite is likely to be true.”

The COVID-19 experiment so far supports him. Most workers[5] and managers[6] are happy with remote working, believe they are performing just as well, and want to continue with it.

Personal contact

But the second argument – the need for personal contact to foster close teamwork – is harder to dismiss.

There is evidence remote workers crave more feedback.

Read more: Informal feedback: we crave it more than ever, and don't care who it's from[7]

As researchers Ethan Bernstein and Ben Waber note in their Harvard Business Review article The Truth About Open Offices[8], published in November 2019, “one of the most robust findings in sociology – proposed long before we had the technology to prove it through data – is that propinquity, or proximity, predicts social interaction”.

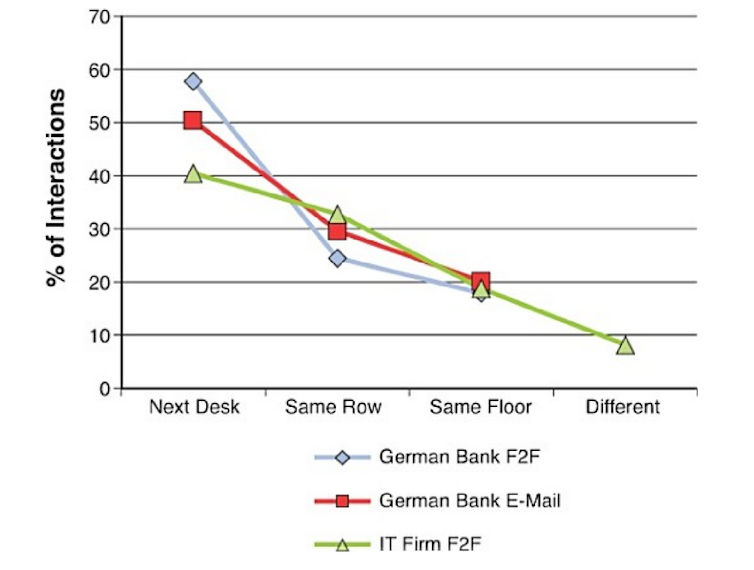

Waber’s research at the MIT Media Lab demonstrated the probability that any two workers will interact – either in person or electronically – is directly proportional to the distance between their desks. In his 2013 book People Analytics[9] he includes the following results from a bank and information technology company.

Be Waber, People Analytics: How Social sensing technology will transform business and what it tell us about the future of wok, FT Press, 2013

Experiments in collaboration

Interest in fostering collaboration has sometimes led to disastrous workplace experiments. One was the building Frank Gehry designed for the Chiat/Day advertising agency in the late 1980s.

Agency boss Jay Chiat envisioned his headquarters as a futuristic step into “flexible work” – but workers hated[10] the lack of personal spaces.

Be Waber, People Analytics: How Social sensing technology will transform business and what it tell us about the future of wok, FT Press, 2013

Experiments in collaboration

Interest in fostering collaboration has sometimes led to disastrous workplace experiments. One was the building Frank Gehry designed for the Chiat/Day advertising agency in the late 1980s.

Agency boss Jay Chiat envisioned his headquarters as a futuristic step into “flexible work” – but workers hated[10] the lack of personal spaces.

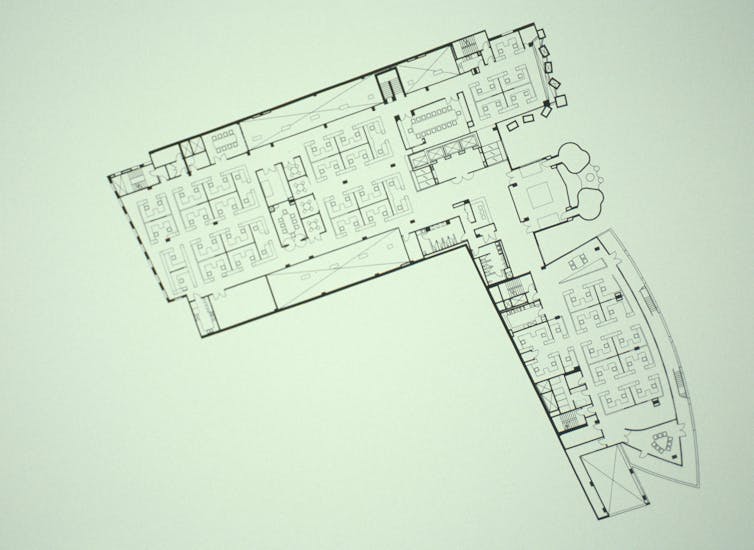

Less impressive inside: the floor plan for the Chiat/Day building in Venice, California.

MIT Libraries, CC BY-NC[11][12]

Less dystopian was the Pixar Animation Studios headquarters opened in 2000. Steve Jobs, majority shareholder and chief executive, oversaw the project. He took a keen interest in things like the placement of bathrooms[13], accessed through the building’s central atrium. “We wanted to find a way to force people to come together,” he said, “to create a lot of arbitrary collisions of people”.

Less impressive inside: the floor plan for the Chiat/Day building in Venice, California.

MIT Libraries, CC BY-NC[11][12]

Less dystopian was the Pixar Animation Studios headquarters opened in 2000. Steve Jobs, majority shareholder and chief executive, oversaw the project. He took a keen interest in things like the placement of bathrooms[13], accessed through the building’s central atrium. “We wanted to find a way to force people to come together,” he said, “to create a lot of arbitrary collisions of people”.

The atrium of Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, California,

Jason Pratt/Flickr, CC BY-SA[14][15]

Yet Bernstein and Waber’s research shows propinquity is also strong in “campus” buildings designed to promote “serendipitous interaction”. For increased interactions, they say, workers should be “ideally on the same floor”.

Being apart

How to balance the organisational forces pulling us together with the health forces pushing social distancing?

We know COVID-19 spreads most easily between people in enclosed spaces for extended periods. In Britain, research by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine shows workplaces are the most common transmission path for adults aged 20 to 50[16].

Read more:

As coronavirus restrictions ease, here's how you can navigate public transport as safely as possible[17]

We may have to get used to wearing masks along with plenty of hand sanitising[18] and disinfecting of high-traffic areas and shared facilities, from keyboards to kitchens. Every door knob and lift button is an issue.

But space is the final frontier.

It’s going to take more than vacating every second desk or imposing barriers like cubicle walls, which largely defeat the point of open-plan offices.

The atrium of Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, California,

Jason Pratt/Flickr, CC BY-SA[14][15]

Yet Bernstein and Waber’s research shows propinquity is also strong in “campus” buildings designed to promote “serendipitous interaction”. For increased interactions, they say, workers should be “ideally on the same floor”.

Being apart

How to balance the organisational forces pulling us together with the health forces pushing social distancing?

We know COVID-19 spreads most easily between people in enclosed spaces for extended periods. In Britain, research by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine shows workplaces are the most common transmission path for adults aged 20 to 50[16].

Read more:

As coronavirus restrictions ease, here's how you can navigate public transport as safely as possible[17]

We may have to get used to wearing masks along with plenty of hand sanitising[18] and disinfecting of high-traffic areas and shared facilities, from keyboards to kitchens. Every door knob and lift button is an issue.

But space is the final frontier.

It’s going to take more than vacating every second desk or imposing barriers like cubicle walls, which largely defeat the point of open-plan offices.

Shutterstock

An alternative vision comes from real-estate services company Cushman & Wakefield. Its “6 feet office” concept includes more space between desks and lots of visual cues to remind coworkers to maintain physical distances.

Read more:

Vital Signs: rules are also signals, which is why easing social distancing is such a problem[19]

Of course, to do anything like this in most offices will require a proportion of staff working at home on any given day. It will also mean then end of the individual desk for most.

This part may the hardest to handle. We like our personal spaces.

We’ll need to balance the sacrifice of sharing spaces against the advantages of working away from the office while still getting to see colleagues in person. We’ll need new arrangements for storing personal items beyond the old locker, and “handover” protocols for equipment and furniture.

Offices will also need to need more private spaces for greater use of video conferencing and the like. These sorts of collaborative tools don’t work well if you can’t insulate yourself from distractions.

But there’s a huge potential upside with the new open office. A well-managed rotation of office days and seating arrangements could help us get to know more of those colleagues who, because they used to sit a few too many desks away, we rarely talked to.

Read more:

Goodbye to the crowded office: how coronavirus will change the way we work together[20]

It might just mean the open-plan office finally finds its mojo.

Shutterstock

An alternative vision comes from real-estate services company Cushman & Wakefield. Its “6 feet office” concept includes more space between desks and lots of visual cues to remind coworkers to maintain physical distances.

Read more:

Vital Signs: rules are also signals, which is why easing social distancing is such a problem[19]

Of course, to do anything like this in most offices will require a proportion of staff working at home on any given day. It will also mean then end of the individual desk for most.

This part may the hardest to handle. We like our personal spaces.

We’ll need to balance the sacrifice of sharing spaces against the advantages of working away from the office while still getting to see colleagues in person. We’ll need new arrangements for storing personal items beyond the old locker, and “handover” protocols for equipment and furniture.

Offices will also need to need more private spaces for greater use of video conferencing and the like. These sorts of collaborative tools don’t work well if you can’t insulate yourself from distractions.

But there’s a huge potential upside with the new open office. A well-managed rotation of office days and seating arrangements could help us get to know more of those colleagues who, because they used to sit a few too many desks away, we rarely talked to.

Read more:

Goodbye to the crowded office: how coronavirus will change the way we work together[20]

It might just mean the open-plan office finally finds its mojo.

References

- ^ The Washington Post (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ in 2015 (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff: Options for Tomorrow (dl.acm.org)

- ^ 50 years of bold predictions about remote work: it isn't all about technology (theconversation.com)

- ^ workers (www.businessinsider.com.au)

- ^ managers (theconversation.com)

- ^ Informal feedback: we crave it more than ever, and don't care who it's from (theconversation.com)

- ^ The Truth About Open Offices (hbr.org)

- ^ People Analytics (www.humanyze.com)

- ^ workers hated (www.wired.com)

- ^ MIT Libraries (dome.mit.edu)

- ^ CC BY-NC (creativecommons.org)

- ^ placement of bathrooms (www.independent.co.uk)

- ^ Jason Pratt/Flickr (www.flickr.com)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ 20 to 50 (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ As coronavirus restrictions ease, here's how you can navigate public transport as safely as possible (theconversation.com)

- ^ hand sanitising (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ Vital Signs: rules are also signals, which is why easing social distancing is such a problem (theconversation.com)

- ^ Goodbye to the crowded office: how coronavirus will change the way we work together (theconversation.com)

Authors: Andrew Wallace, Program director of Interior Architecture, University of South Australia