A temporary income tax hike is the bitter but equitable pill Australia should swallow

- Written by Jonathan Karnon, Professor of Health Economics, Flinders University

We’re all in this pandemic together. But we’re currently leaving it to a small proportion of the community to shoulder most of the economic pain.

It’s an approach that’s compounding social and intergenerational inequity.

To date the Australian government has committed A$320 billion to support households and businesses[1] during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Commonwealth’s net debt had been projected to peak this year at $392 billion[2] and then decline. Now that debt is set to almost double.

Read more: Vital Signs: Scott Morrison is steering in the right direction, but we're going to need a bigger boat[3]

Paying the debt will likely take decades. The burden will fall mostly on younger generations, through higher taxes or reduced public services such as health care and education.

Younger workers are also bearing the brunt of the immediate economic effects. Industries with the biggest proportion of young workers[4] have been hit hard. In arts and recreation services, a quarter of workers are under the age of 25. In retail it’s about a third. In accommodation and food services it’s almost half.

In the past, governments have imposed temporary levies after natural disasters[5] to pay for recovery efforts.

But the peculiar dynamics of this crisis open the opportunity to introduce a temporary levy now. This would enable those with secure incomes to share the pain and reduce the double impost on the younger generation.

Levy time

A temporary income tax levy is not unprecedented.

In 2014 the federal government implemented the “temporary budget repair levy[6]” to reduce the budget deficit (then A$37 billion). Gross national debt was about $320 billion. The levy increased the marginal tax rate on the top income bracket (more than $180,000 a year) from 45% to 47%. It collected about A$3 billion over three years.

Given the magnitude of the deficit we now face, a similar levy makes sense.

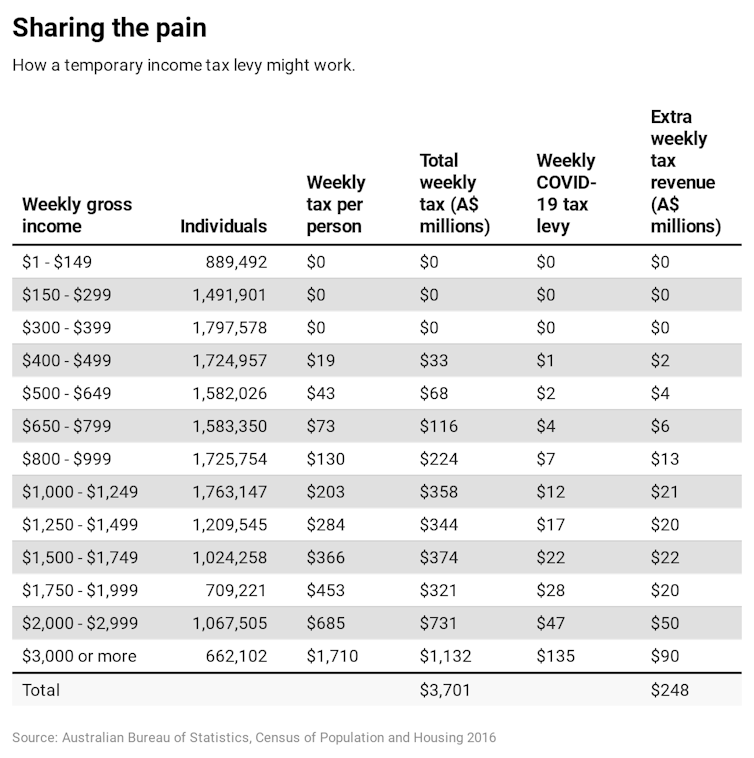

An example levy is illustrated in the table below (based on income tax data from 2016). A 1% levy is applied to annual income between A$18,200 and A$37,000, a 2% levy to income between A$37,000 and A$90,000, a 3% levy up to A$180,000, and a 4% levy to income of more than A$180,000.

For someone on a median full-time income of A$1,463 a week[7], this would mean paying an extra A$17 a week in income tax.

Over a six-month period such a levy would raise about A$6.5 billion.

Consumption block

The main argument against raising income taxes is that it reduces incentives to work and lowers consumers’ disposable income, which dampens economic activity (and ultimately government revenue).

This, and the politics of tax, means governments usually wouldn’t dream of raising taxes during an economic crisis, because that would further reduce consumer spending and compound the downturn.

But the COVID-19 economic crisis is unique. It is suppressing spending by those with secure incomes because people are staying home.

Analysis published by The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age[8] shows consumer spending fell to 13% below normal in late March. One-off government stimulus payments[9] totalling A$5 billion reversed the downward trend in the first week of April. However, the effect of the one-off stimulus payments is likely to be temporary as higher-income earners, who didn’t receive a stimulus payment, continued to reduce their spending.

If people are spending less because there are fewer opportunities to spend, this novel aspect of the crisis reduces the likelihood a temporary increase in the income tax levy would have any negative economic effect.

Positive effects

Right now the costs of the COVID-19 crisis are being disproportionately borne by a small proportion of the population – the 700,000 Australians who have lost their jobs and about the same number relying on the JobKeeper wage subsidy.

Many of those who have lost their jobs were already in low-paid and insecure jobs.

As previous research on the longer-term effects of natural disasters[10] has found, these types of economic shocks widen inequalities, with most people never making up the income they lose. A levy would reduce this inequity.

Read more:

More Australians are worried about a recession and an increasingly selfish society than about coronavirus itself[11]

An advantage of introducing a levy during the crisis is there is clear time-frame to end it. It could be tied to social distancing regulations, ending when spending patterns return to normal.

Alternatively, the government could set a specific date to review the levy. It has already done this for funding initiatives such as telehealth consults[12] during the crisis.

For someone on a median full-time income of A$1,463 a week[7], this would mean paying an extra A$17 a week in income tax.

Over a six-month period such a levy would raise about A$6.5 billion.

Consumption block

The main argument against raising income taxes is that it reduces incentives to work and lowers consumers’ disposable income, which dampens economic activity (and ultimately government revenue).

This, and the politics of tax, means governments usually wouldn’t dream of raising taxes during an economic crisis, because that would further reduce consumer spending and compound the downturn.

But the COVID-19 economic crisis is unique. It is suppressing spending by those with secure incomes because people are staying home.

Analysis published by The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age[8] shows consumer spending fell to 13% below normal in late March. One-off government stimulus payments[9] totalling A$5 billion reversed the downward trend in the first week of April. However, the effect of the one-off stimulus payments is likely to be temporary as higher-income earners, who didn’t receive a stimulus payment, continued to reduce their spending.

If people are spending less because there are fewer opportunities to spend, this novel aspect of the crisis reduces the likelihood a temporary increase in the income tax levy would have any negative economic effect.

Positive effects

Right now the costs of the COVID-19 crisis are being disproportionately borne by a small proportion of the population – the 700,000 Australians who have lost their jobs and about the same number relying on the JobKeeper wage subsidy.

Many of those who have lost their jobs were already in low-paid and insecure jobs.

As previous research on the longer-term effects of natural disasters[10] has found, these types of economic shocks widen inequalities, with most people never making up the income they lose. A levy would reduce this inequity.

Read more:

More Australians are worried about a recession and an increasingly selfish society than about coronavirus itself[11]

An advantage of introducing a levy during the crisis is there is clear time-frame to end it. It could be tied to social distancing regulations, ending when spending patterns return to normal.

Alternatively, the government could set a specific date to review the levy. It has already done this for funding initiatives such as telehealth consults[12] during the crisis.

References

- ^ A$320 billion to support households and businesses (treasury.gov.au)

- ^ $392 billion (budget.gov.au)

- ^ Vital Signs: Scott Morrison is steering in the right direction, but we're going to need a bigger boat (theconversation.com)

- ^ biggest proportion of young workers (docs.employment.gov.au)

- ^ after natural disasters (www.ato.gov.au)

- ^ temporary budget repair levy (theconversation.com)

- ^ A$1,463 a week (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ One-off government stimulus payments (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ longer-term effects of natural disasters (theconversation.com)

- ^ More Australians are worried about a recession and an increasingly selfish society than about coronavirus itself (theconversation.com)

- ^ telehealth consults (theconversation.com)

Authors: Jonathan Karnon, Professor of Health Economics, Flinders University