New year, new strategy? Unheralded change to budget targets creates space for stimulus

- Written by Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute

In public, the government is crab-walking away from its commitment to a budget surplus, saying since the bushfires that other things have become more important.

Asked directly on Tuesday whether he was prepared to sacrifice this year’s projected surplus to help the bushfire recovery effort, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said:

Our focus is on delivering the services and support to people in need. That’s what we’ve been doing.

But less-publicly, and little noticed in the pre-Christmas release of the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook just before Christmas, the government has quietly buried long-standing targets for restraining spending.

Jettisoning these targets provides it with more wriggle room to increase spending to respond to things such as the bushfires and to boost the economy should it need to in 2020 and beyond.

Read more: 5 things MYEFO tells us about the economy and the nation’s finances[1]

Under the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998 every government must release a fiscal strategy statement alongside the Budget.

The statement is a list of the government’s budget targets. One long-standing target is “to achieve surpluses on average over the economic cycle”. Others relate to spending, tax collections, and public debt.

They are not binding but they provide a useful guide to the government’s thinking.

A looser straitjacket

Revisions to these targets can signal changes to the government’s approach.

In the pre-Christmas Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO), the government significantly scaled back its targets – both in number and ambition.

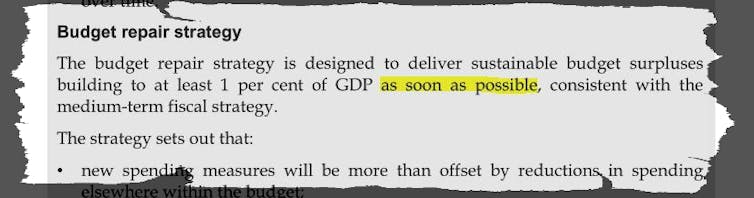

For example, the budget repair strategy it adopted in 2014 committed it to “deliver budget surpluses building to at least 1% of GDP by 2023-24”.

Read more: Surplus before spending. Frydenberg's risky MYEFO strategy[2]

The strategy has been reproduced in every budget since then, although in 2017 the 2023-24 deadline was extended to “as soon as possible”.

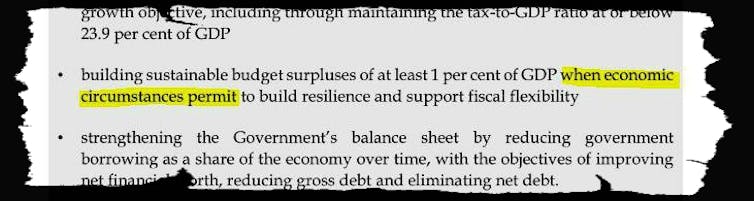

In December’s MYEFO more wriggle room was added, with the surpluses of at least 1% of GDP to be reached only “when economic circumstances permit”.

Spot the difference

2019 Budget[3]

2019 Budget[3]

2019 MYEFO[4]

Another component of the original repair strategy was that “new spending initiatives will be more than offset by reductions in spending elsewhere in the budget”.

In other words: if the government wanted to announce a new spending policy, it had to find savings elsewhere to cover the cost.

Targets missing

This target does not appear in MYEFO. A softer replacement says the government intends to “pursue budget savings to make room for spending priorities”.

This relaxing of the purse strings is already evident: the new spending measures in MYEFO on aged-care home packages, bringing forward infrastructure spending, and drought assistance are significant costs that were not paid for by spending reductions elsewhere.

Nor has the government provided any indication that its bushfire relief measures will be funded through savings.

Gone: the commitment to cut the government’s share of the economy over time

2019 MYEFO[4]

Another component of the original repair strategy was that “new spending initiatives will be more than offset by reductions in spending elsewhere in the budget”.

In other words: if the government wanted to announce a new spending policy, it had to find savings elsewhere to cover the cost.

Targets missing

This target does not appear in MYEFO. A softer replacement says the government intends to “pursue budget savings to make room for spending priorities”.

This relaxing of the purse strings is already evident: the new spending measures in MYEFO on aged-care home packages, bringing forward infrastructure spending, and drought assistance are significant costs that were not paid for by spending reductions elsewhere.

Nor has the government provided any indication that its bushfire relief measures will be funded through savings.

Gone: the commitment to cut the government’s share of the economy over time

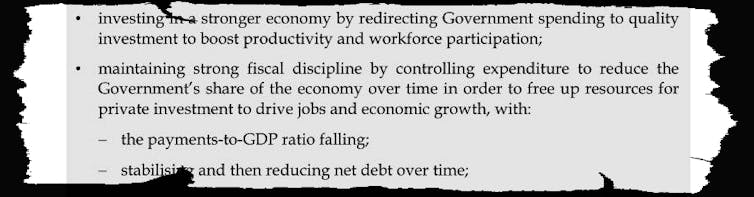

2019 Budget[5]

The budget repair strategy also required improvements in the budget position due to favourable economic circumstances to be “banked to the bottom line”. That target has now been removed all together.

The medium-term (10-year) fiscal strategy has also been amended to remove some of the more ambitious spending-control targets.

One was to reduce the government’s share of the economy over time.

That target has now gone, even though shrinking government spending as a share of the economy is crucial to the budget projections of growing surpluses and declining net debt over the decade.

The obvious question is – why?

The government is making big spending easier

The government might argue that it no longer needs a budget repair strategy because it expects to a deliver a surplus this year.

But its strategy was always more ambitious than a single surplus.

It wanted to reach continuing surpluses of 1% of GDP. Surplus forecasts of between 0.2% and 0.4% of GDP over the next four years indicate it is still well short of achieving them.

More likely is that it recognises that some of its targets were going to be difficult to meet.

Read more:

The big budget question is why the surplus wasn't big[6]

It has already failed on a number of occasions[7] to offset new spending with savings. Around half[8] of this year’s upside from stronger-than-expected commodity prices and employment growth was used to fund tax cuts and extra spending rather than banked to the budget bottom line.

As the Parliamentary Budget Office[9] has pointed out, it becomes even harder to hold down spending as the budget improves.

This is all the truer amid the need for bushfire reconstruction.

It’s better to shift goal posts than repeatedly fail to score

Another possible explanation is that the government is clearing the way for fiscal stimulus. To date it has relied on the efforts of the Reserve Bank and state governments to boost lacklustre economic growth.

Reserve Bank governor Phil Lowe, along with many economists[10], has argued that it should do more.

In taking off its self-imposed spending straitjacket, it is giving itself room to heed the governor’s call.

Read more:

We asked 13 economists how to fix things. All back the RBA governor over the treasurer[11]

2019 Budget[5]

The budget repair strategy also required improvements in the budget position due to favourable economic circumstances to be “banked to the bottom line”. That target has now been removed all together.

The medium-term (10-year) fiscal strategy has also been amended to remove some of the more ambitious spending-control targets.

One was to reduce the government’s share of the economy over time.

That target has now gone, even though shrinking government spending as a share of the economy is crucial to the budget projections of growing surpluses and declining net debt over the decade.

The obvious question is – why?

The government is making big spending easier

The government might argue that it no longer needs a budget repair strategy because it expects to a deliver a surplus this year.

But its strategy was always more ambitious than a single surplus.

It wanted to reach continuing surpluses of 1% of GDP. Surplus forecasts of between 0.2% and 0.4% of GDP over the next four years indicate it is still well short of achieving them.

More likely is that it recognises that some of its targets were going to be difficult to meet.

Read more:

The big budget question is why the surplus wasn't big[6]

It has already failed on a number of occasions[7] to offset new spending with savings. Around half[8] of this year’s upside from stronger-than-expected commodity prices and employment growth was used to fund tax cuts and extra spending rather than banked to the budget bottom line.

As the Parliamentary Budget Office[9] has pointed out, it becomes even harder to hold down spending as the budget improves.

This is all the truer amid the need for bushfire reconstruction.

It’s better to shift goal posts than repeatedly fail to score

Another possible explanation is that the government is clearing the way for fiscal stimulus. To date it has relied on the efforts of the Reserve Bank and state governments to boost lacklustre economic growth.

Reserve Bank governor Phil Lowe, along with many economists[10], has argued that it should do more.

In taking off its self-imposed spending straitjacket, it is giving itself room to heed the governor’s call.

Read more:

We asked 13 economists how to fix things. All back the RBA governor over the treasurer[11]

References

- ^ 5 things MYEFO tells us about the economy and the nation’s finances (theconversation.com)

- ^ Surplus before spending. Frydenberg's risky MYEFO strategy (theconversation.com)

- ^ 2019 Budget (budget.gov.au)

- ^ 2019 MYEFO (budget.gov.au)

- ^ 2019 Budget (budget.gov.au)

- ^ The big budget question is why the surplus wasn't big (theconversation.com)

- ^ a number of occasions (theconversation.com)

- ^ half (theconversation.com)

- ^ Parliamentary Budget Office (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ along with many economists (theconversation.com)

- ^ We asked 13 economists how to fix things. All back the RBA governor over the treasurer (theconversation.com)

Authors: Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute