What we missed while we looked away -- the growth of long‐term unemployment

- Written by Jeff Borland, Professor of Economics, University of Melbourne

Australia took its eyes off long-term unemployment, for what it thought were good reasons.

Long-term unemployment is defined as unemployment for more than 12 months in a row.

In the early 1990s, after the “recession we had to have[1]”, long-term unemployment grew to a postwar high of 4% and became a major concern for the government amid fears that once Australians had became long-term unemployed, they would never easily get back to work.

Over time, that concern lessened.

Strong economic growth delivered a steady decline in the overall rate of unemployment and, as a consequence, long-term unemployment.

With the long-term rate low, we looked away…

By the time the financial crisis hit in 2008, Australia’s long-term unemployment rate was down to just 0.6%. After the crisis, our lack of attention continued.

The crisis had caused only a relatively small increase in unemployment, and it seemed reasonable to assume that it hadn’t caused much of an uptick in long-term unemployment.

In absolute terms, it hadn’t. Today, long-term unemployment is 1.25%, still way below its peak in the early 1990s.

But that figure of 1.25% demands closer attention.

It is about 0.3 percentage points higher than would have been the case for the same unemployment rate a few years earlier.

…and kept looking away…

Those few fractions of a percentage point mightn’t seem like much, but they add up to 41,000 more long-term unemployed Australians than would be expected.

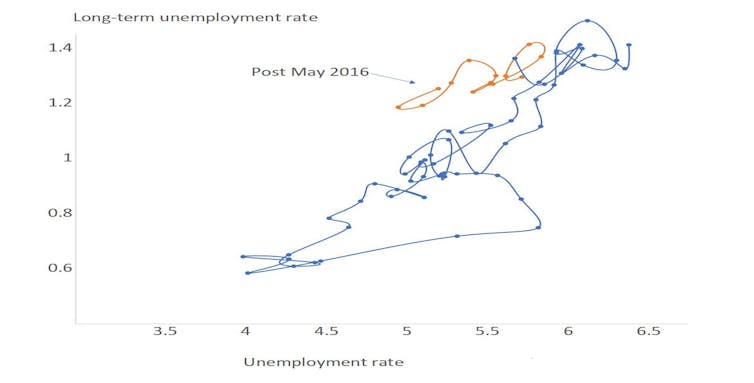

The surprising growth in long-term unemployment relative to unemployment can be seen in the figure below, which shows rates of unemployment and long-term unemployment from 2003 onwards.

Unemployment rates and long-term unemployment rates, 2003-19

ABS 6291.0.55.001 (seasonally adjusted)[2]

It is clear that something changed after mid-2016.

Before then, an unemployment rate of 5% meant a rate of long-term unemployment of about 1%. After then it has meant a long-term unemployment rate of about 1.3%.

While the change has become most apparent since 2016, I argue in my recent briefing on this topic[3] that it began earlier, in the years between 2009 and 2016.

During those seven years, the overall rate of unemployment changed little.

…while something changed

Standard theories predict that if the overall rate of unemployment remains stable, the rate of long-term unemployment should also remain stable.

But the rate of long-term unemployment virtually doubled from 0.7% to 1.35% during those seven years, meaning the proportion of the unemployed who were long-term unemployed climbed from 13% to 23%.

The growth in long-term unemployment has been pervasive – affecting male and female jobseekers equally, and all age categories – although young jobseekers seem to have been the most affected.

At this stage, the reasons for the increase remain unclear.

Low wage growth deepens the mystery

Paradoxically, it makes Australia’s current low rate of wage growth even harder to understand.

Standard theories characterise the long-term unemployed as being less immediately employable than the short-term unemployed, meaning that as long-term unemployment grows as a proportion of total unemployment, employers will try to fill vacancies from a smaller and smaller pool of short-term unemployed, making it easier for existing workers to extract higher wages.

If this is happening, it is being more than offset by something else.

Read more:

Buckle up. 2019-20 survey finds the economy weak and heading down, and that's ahead of surprises[4]

What this development certainly does mean is that we ought to be concentrating more on getting the long-term unemployed back into work. Fortuitously, this is already happening.

In 2018 an expert panel commissioned by the then Commonwealth Department of Jobs and Small Business recommended rebalancing of employment services towards jobseekers facing the highest barriers to employment[5].

The increasingly chunk of the unemployed who are long-term unemployed makes the need for such a shift more critical.

ABS 6291.0.55.001 (seasonally adjusted)[2]

It is clear that something changed after mid-2016.

Before then, an unemployment rate of 5% meant a rate of long-term unemployment of about 1%. After then it has meant a long-term unemployment rate of about 1.3%.

While the change has become most apparent since 2016, I argue in my recent briefing on this topic[3] that it began earlier, in the years between 2009 and 2016.

During those seven years, the overall rate of unemployment changed little.

…while something changed

Standard theories predict that if the overall rate of unemployment remains stable, the rate of long-term unemployment should also remain stable.

But the rate of long-term unemployment virtually doubled from 0.7% to 1.35% during those seven years, meaning the proportion of the unemployed who were long-term unemployed climbed from 13% to 23%.

The growth in long-term unemployment has been pervasive – affecting male and female jobseekers equally, and all age categories – although young jobseekers seem to have been the most affected.

At this stage, the reasons for the increase remain unclear.

Low wage growth deepens the mystery

Paradoxically, it makes Australia’s current low rate of wage growth even harder to understand.

Standard theories characterise the long-term unemployed as being less immediately employable than the short-term unemployed, meaning that as long-term unemployment grows as a proportion of total unemployment, employers will try to fill vacancies from a smaller and smaller pool of short-term unemployed, making it easier for existing workers to extract higher wages.

If this is happening, it is being more than offset by something else.

Read more:

Buckle up. 2019-20 survey finds the economy weak and heading down, and that's ahead of surprises[4]

What this development certainly does mean is that we ought to be concentrating more on getting the long-term unemployed back into work. Fortuitously, this is already happening.

In 2018 an expert panel commissioned by the then Commonwealth Department of Jobs and Small Business recommended rebalancing of employment services towards jobseekers facing the highest barriers to employment[5].

The increasingly chunk of the unemployed who are long-term unemployed makes the need for such a shift more critical.

References

- ^ recession we had to have (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ ABS 6291.0.55.001 (seasonally adjusted) (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ briefing on this topic (drive.google.com)

- ^ Buckle up. 2019-20 survey finds the economy weak and heading down, and that's ahead of surprises (theconversation.com)

- ^ highest barriers to employment (docs.employment.gov.au)

Authors: Jeff Borland, Professor of Economics, University of Melbourne