How English-speaking countries upended the trade-off between babies and jobs without even trying

- Written by Daniel Dinale, PhD Candidate, University of Sydney

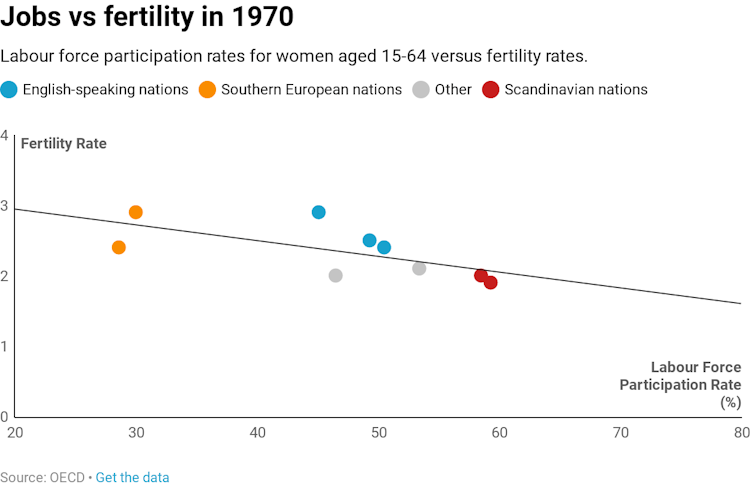

The traditional understanding of women’s economic empowerment is that, as participation in paid employment increases, fertility decreases.

This was certainly true in industrialised nations up to the early 1980s.

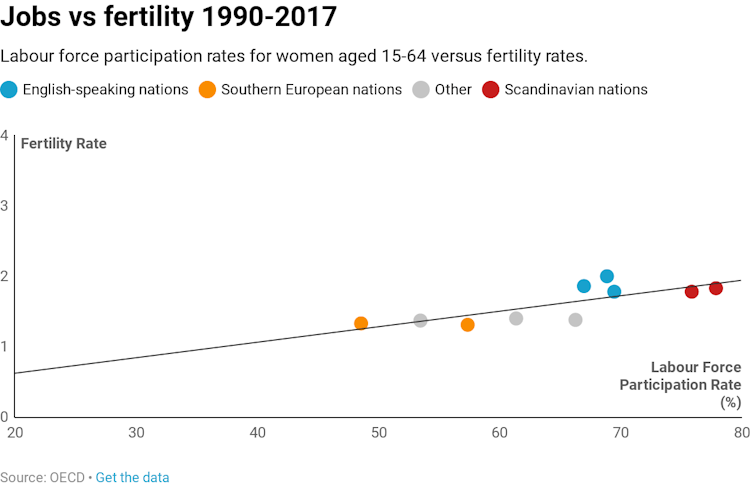

But then things began to change[1]. OECD data now shows a positive correlation between higher female labour participation and higher fertility rates.

This fact may not be widely known, but it has been well-documented. Why it has occurred, though, is more of a mystery – and the focus of our research.

Scandinavian nations have been at the forefront of the reversal – but that’s not surprising. Countries like Sweden and Denmark have strong state support for working mothers and high cultural acceptance of gender equality. It’s easy to see how they have made it easier for women to reconcile family and career.

The puzzle is that English-speaking nations aren’t too far behind the Scandinavian countries, despite high childcare costs and relatively little policy to support working mothers.

Our research points to a set of factors in Anglophone economies not typically identified as tools for women’s empowerment: in particular, flexible labour markets.

Understanding all the factors that contribute to a positive relationship between paid employment and fertility is profoundly important for policy makers the world over. It may help countries such as Japan, which is grappling with the consequences of birth rates falling below population replacement level. It can also help countries such as India, where female economic participation rates remain stubbornly low[2].

Read more: The conspicuous absence of women in India’s labour force[3]

Reversing the trend

The following graph shows the situation in nine industrialised nations, exemplifying different varieties of capitalism, government policy and cultural clusters, in 1970: the trend line indicates higher female labour force participation is associated with a lower fertility rate.

This relationship began to change in the mid-1980s[4]. Now, across the developed world, greater female participation in paid work is associated with a higher national fertility rate.

This relationship began to change in the mid-1980s[4]. Now, across the developed world, greater female participation in paid work is associated with a higher national fertility rate.

This shows having babies and having careers need not be mutually exclusive – that it is possible, in economic terms, for a nation to produce and reproduce.

Leading the way have been Sweden and Denmark. Their welfare systems provide generous conditions such as parental leave and subsidies for childcare. Sweden’s public expenditure on childcare is 1.1% of total national income[5] – the highest in the world.

These nations are also characterised by a relatively high degree of gender equality within households[6]. Men are more likely to share the responsibilities of looking after children, for example, making it easier for their partners to pursue careers.

Flexibility is a key

So what about developed English-speaking economies? These nations have relatively limited support for working parents[7], especially when compared with social democratic nations like Denmark or Sweden.

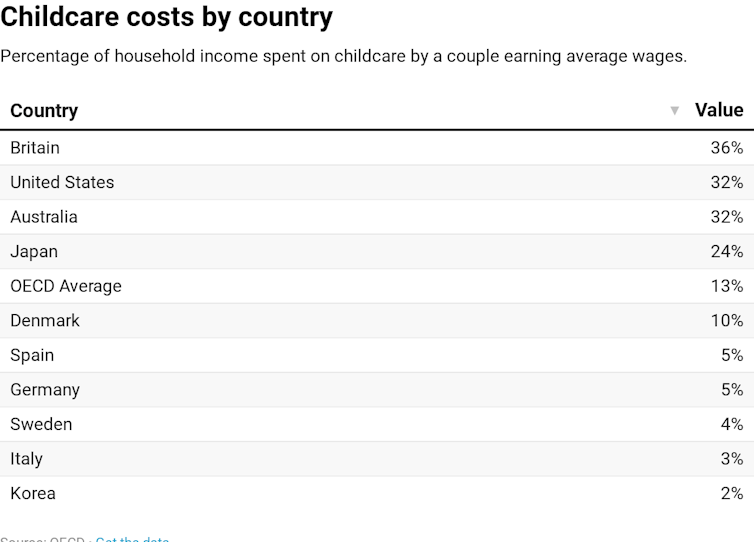

Australia, Britain, New Zealand and the United States are among the most expensive in the world for childcare, according to 2018 data from the OECD[8]. On average, in these countries couples spend about third of their combined income on childcare costs. This compares to the OECD average of 13%, and 4% in Sweden.

This shows having babies and having careers need not be mutually exclusive – that it is possible, in economic terms, for a nation to produce and reproduce.

Leading the way have been Sweden and Denmark. Their welfare systems provide generous conditions such as parental leave and subsidies for childcare. Sweden’s public expenditure on childcare is 1.1% of total national income[5] – the highest in the world.

These nations are also characterised by a relatively high degree of gender equality within households[6]. Men are more likely to share the responsibilities of looking after children, for example, making it easier for their partners to pursue careers.

Flexibility is a key

So what about developed English-speaking economies? These nations have relatively limited support for working parents[7], especially when compared with social democratic nations like Denmark or Sweden.

Australia, Britain, New Zealand and the United States are among the most expensive in the world for childcare, according to 2018 data from the OECD[8]. On average, in these countries couples spend about third of their combined income on childcare costs. This compares to the OECD average of 13%, and 4% in Sweden.

So why do these countries trail the Scandinavian countries only slightly, combining relatively high female employment rates with relatively high fertility?

We suggest the answer may lie in the structure of their economies.

Their manufacturing sectors – traditional bastions of male employment – have declined. But their services sectors have expanded relatively more. In the United States, for example, 80% of all employment is in the services sector, compared with 70% in Germany and 68% in Italy[9].

One advantage of the services sector is that, on average, it is more tolerant of employment interruption[10]. This makes it friendlier to the need of mothers. In the US, the sector employs 91% of women[11], compared with 68.5% of men[12].

The sector also provides more opportunities for workers with “general skills”. Teachers, for example, have skills that can be transferred across schools, and are likely to remain valuable despite interruptions from the labour market.

Traditional jobs, traditional attitudes

The economies of Germany and Japan have maintained their manufacturing bases – but perhaps at the cost of lower fertility. Manufacturing jobs tend to favour continuous and uninterrupted employment[13], and therefore better suit men, not women trying to juggle paid work and family.

Countries like Spain and Italy, meanwhile, have low childcare costs but also tend to retain more traditional attitudes towards gender roles. Less support from men in the home to sharing responsibilities traditionally done by mothers seems, counter-intuitively, to suppress both female labour force participation and the birth rate.

Read more:

How many humans tomorrow? The United Nations revises its projections[14]

The lesson from Scandinavian nations is that generous childcare and other parental benefits can help boost female employment and women’s ability to have children[15].

The lesson from English-speaking nations is not everything is down to government. The structure of the labour market is also crucial for women to balance employment and family commitments, and to be free to choose what suits them best.

So why do these countries trail the Scandinavian countries only slightly, combining relatively high female employment rates with relatively high fertility?

We suggest the answer may lie in the structure of their economies.

Their manufacturing sectors – traditional bastions of male employment – have declined. But their services sectors have expanded relatively more. In the United States, for example, 80% of all employment is in the services sector, compared with 70% in Germany and 68% in Italy[9].

One advantage of the services sector is that, on average, it is more tolerant of employment interruption[10]. This makes it friendlier to the need of mothers. In the US, the sector employs 91% of women[11], compared with 68.5% of men[12].

The sector also provides more opportunities for workers with “general skills”. Teachers, for example, have skills that can be transferred across schools, and are likely to remain valuable despite interruptions from the labour market.

Traditional jobs, traditional attitudes

The economies of Germany and Japan have maintained their manufacturing bases – but perhaps at the cost of lower fertility. Manufacturing jobs tend to favour continuous and uninterrupted employment[13], and therefore better suit men, not women trying to juggle paid work and family.

Countries like Spain and Italy, meanwhile, have low childcare costs but also tend to retain more traditional attitudes towards gender roles. Less support from men in the home to sharing responsibilities traditionally done by mothers seems, counter-intuitively, to suppress both female labour force participation and the birth rate.

Read more:

How many humans tomorrow? The United Nations revises its projections[14]

The lesson from Scandinavian nations is that generous childcare and other parental benefits can help boost female employment and women’s ability to have children[15].

The lesson from English-speaking nations is not everything is down to government. The structure of the labour market is also crucial for women to balance employment and family commitments, and to be free to choose what suits them best.

References

- ^ things began to change (link.springer.com)

- ^ remain stubbornly low (data.worldbank.org)

- ^ The conspicuous absence of women in India’s labour force (theconversation.com)

- ^ the mid-1980s (link.springer.com)

- ^ 1.1% of total national income (www.oecd.org)

- ^ gender equality within households (www.oecd.org)

- ^ limited support for working parents (www.jstor.org)

- ^ 2018 data from the OECD (data.oecd.org)

- ^ 70% in Germany and 68% in Italy (data.worldbank.org)

- ^ employment interruption (academic.oup.com)

- ^ 91% of women (data.worldbank.org)

- ^ 68.5% of men (data.worldbank.org)

- ^ employment (www.people.fas.harvard.edu)

- ^ How many humans tomorrow? The United Nations revises its projections (theconversation.com)

- ^ women’s ability to have children (journals.sagepub.com)

Authors: Daniel Dinale, PhD Candidate, University of Sydney