The Reserve Bank will cut rates again and again, until we lift spending and push up prices

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

The Reserve Bank cut interest rates on Tuesday because we aren’t spending or pushing up prices at anything like the rate it would like. And things are even worse than it might have realised.

As the board met in Martin Place in Sydney, in Canberra at 11.30 am the Bureau of Statistics released details of retail spending in April, one month beyond the March quarter figures the bank was using to make its decision.

They show the dollars spent in shops fell in April, slipping 0.1%, notwithstanding weakly growing prices and a more strongly growing population.

The March quarter figures the board was looking at were adjusted for prices. They show that the volume of goods and services bought, but not the amount paid for them, fell in seasonally adjusted terms during the March quarter.

Adjusted for population, the volume bought would have fallen further.

We’ll know more on Wednesday

The Bureau of Statistics will release population-adjusted figures as part of the national accounts on Wednesday.

The figures for the September quarter show that income and spending per person barely grew. The figures for the December quarter show income and spending per person fell.

A second fall in the March quarter will mean two in a row – what some people call a per capita recession.

Australian National Accounts[1]

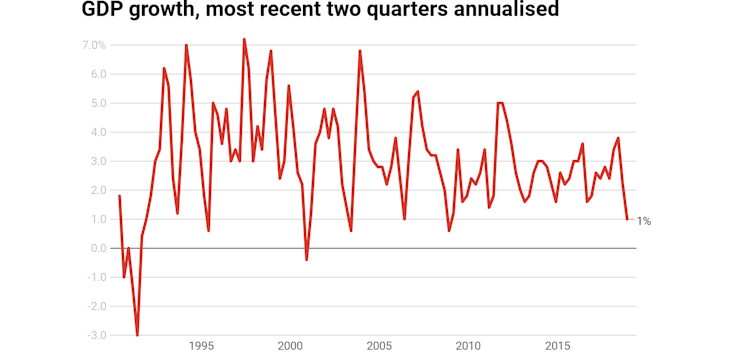

Even unadjusted for population, economic growth is dismal.

During the September and December quarters the economy grew just 0.3% and 0.2%[2] – an annualised rate of just 1%.

That’s well short of the 2.75%[3] the treasury believes we are capable of, and the lower than normal 2.25%[4] it has forecast for the year to June.

Australian National Accounts[1]

Even unadjusted for population, economic growth is dismal.

During the September and December quarters the economy grew just 0.3% and 0.2%[2] – an annualised rate of just 1%.

That’s well short of the 2.75%[3] the treasury believes we are capable of, and the lower than normal 2.25%[4] it has forecast for the year to June.

Australian National Accounts[5]

We’ve been doing it by ourselves. As Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe said in announcing the rates decision[6] on Tuesday:

The main domestic uncertainty continues to be the outlook for household consumption, which is being affected by a protracted period of low income growth and declining housing prices.

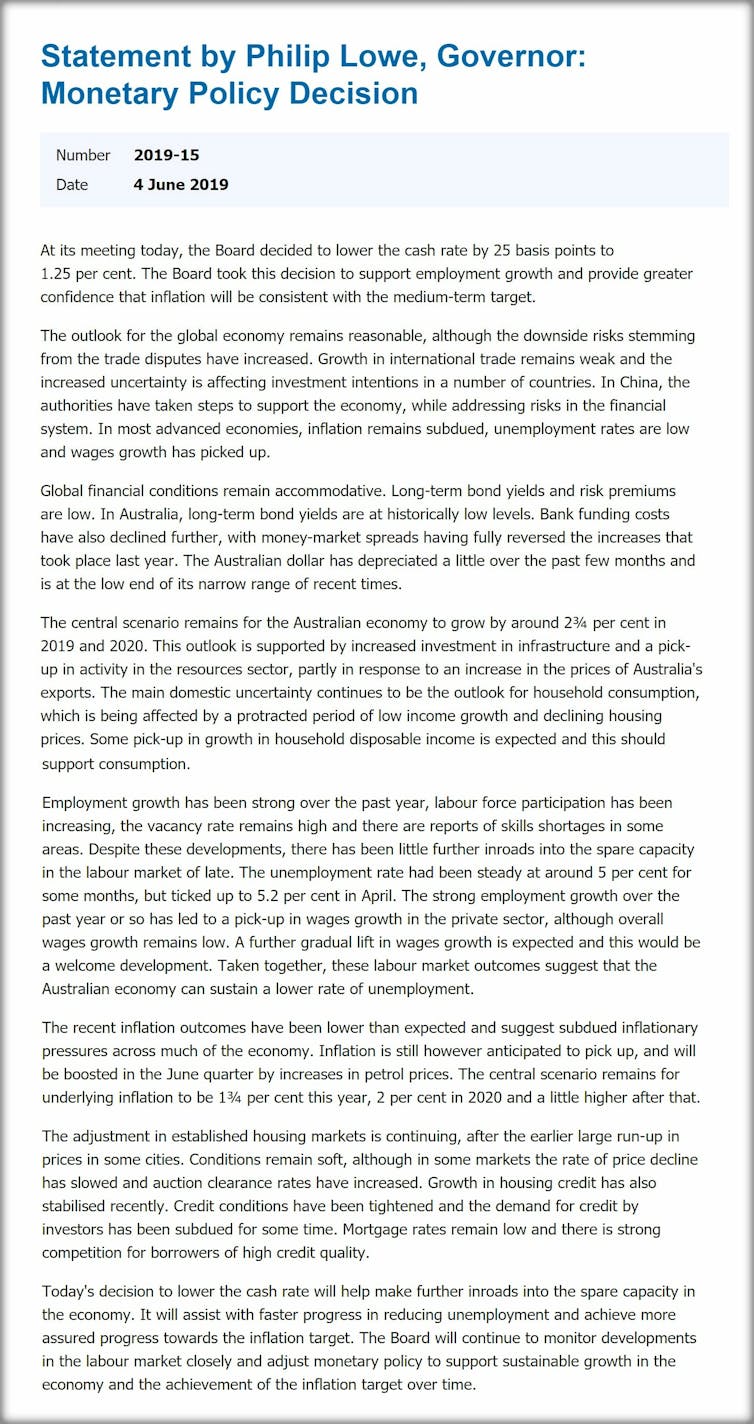

The bank wants both inflation and employment higher, and it wants us to spend more in order to do it. Lower rates should help, although not for everybody[7].

Lowe acknowledged this is a speech to a Sydney business audience on Tuesday night, but he said households paid two dollars in interest for every one dollar of interest they received. So while rate cuts hurt savers, they benefit borrowers by more, and over time should benefit all households by boosting the economy. They also drive the dollar lower, making Australian businesses more competitive.

Tuesday’s cut should free up an extra A$60 a month for a typical mortgage holder. Another one will free up a total of $120.

It’s not much, and there’s doubt about whether it will do much, but interest rates are about the only tool the Reserve Bank has.

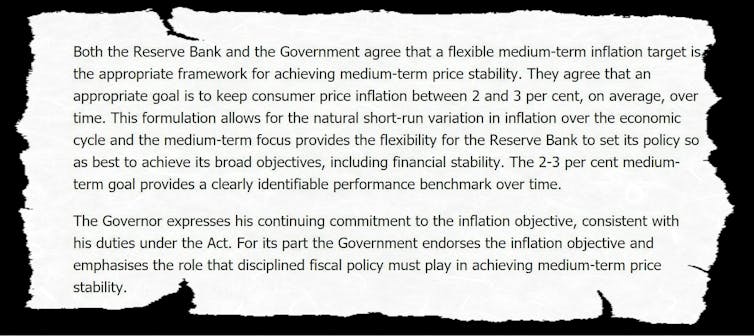

It is required by its agreement with the government to aim for an inflation rate of between 2% and 3%[8], “on average, over time”.

Australian National Accounts[5]

We’ve been doing it by ourselves. As Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe said in announcing the rates decision[6] on Tuesday:

The main domestic uncertainty continues to be the outlook for household consumption, which is being affected by a protracted period of low income growth and declining housing prices.

The bank wants both inflation and employment higher, and it wants us to spend more in order to do it. Lower rates should help, although not for everybody[7].

Lowe acknowledged this is a speech to a Sydney business audience on Tuesday night, but he said households paid two dollars in interest for every one dollar of interest they received. So while rate cuts hurt savers, they benefit borrowers by more, and over time should benefit all households by boosting the economy. They also drive the dollar lower, making Australian businesses more competitive.

Tuesday’s cut should free up an extra A$60 a month for a typical mortgage holder. Another one will free up a total of $120.

It’s not much, and there’s doubt about whether it will do much, but interest rates are about the only tool the Reserve Bank has.

It is required by its agreement with the government to aim for an inflation rate of between 2% and 3%[8], “on average, over time”.

Treasurer and Reserve Bank Governor, Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy, September 19, 2016.

Reserve Bank of Australia[9]

Uncomfortably for Governor Lowe, underlying inflation (abstracting from unusual moves which are quickly reversed) has been below 2% ever since he was appointed governor in late 2016.

Explaining his push for higher inflation to a business audience in Sydney on Tuesday night he said that while adherence to the target was intended to be flexible, that flexibility was “not boundless”.

If inflation stays too low for too long, it is possible that inflation

expectations move lower – that Australians come to expect sub-2% inflation

on an ongoing basis. If this were to happen, it would be harder to achieve the

medium term inflation goal. So we need to guard against this possibility.

He is also required to aim for full employment[10].

He told the business audience that while for some years the bank and others had thought full employment meant an unemployment rate of 5%, the absence of inflation at 5% and the persistence of underemployment (where people wanted more hours) meant it could and should go lower.

Our judgement now is that we can do better than this – that we can sustain an

unemployment rate of 4 point something.

Lower interest rates should help by making it easier to businesses to borrow to expand, and giving consumers something in their pockets to buy from them.

If you don’t succeed…

If that doesn’t happen, the bank will cut again.

Tuesday’s statement as good as said so:

The board will continue to monitor developments in the labour market closely and adjust monetary policy to support sustainable growth in the economy and the achievement of the inflation target over time.

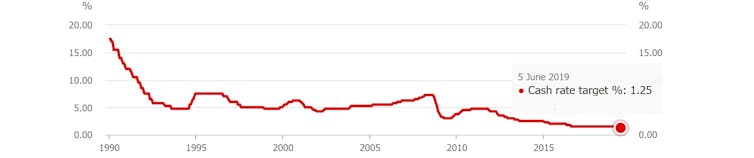

Tuesday’s cut and the next will take the bank into uncharted waters, where its so-called cash rate – what it pays to banks to deposit money with it overnight – is close to zero.

As far as can be discerned it has never been that low in the 100+ years the Reserve Bank has been in operation, originally as the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

Reserve Bank cash rate since 1990

Treasurer and Reserve Bank Governor, Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy, September 19, 2016.

Reserve Bank of Australia[9]

Uncomfortably for Governor Lowe, underlying inflation (abstracting from unusual moves which are quickly reversed) has been below 2% ever since he was appointed governor in late 2016.

Explaining his push for higher inflation to a business audience in Sydney on Tuesday night he said that while adherence to the target was intended to be flexible, that flexibility was “not boundless”.

If inflation stays too low for too long, it is possible that inflation

expectations move lower – that Australians come to expect sub-2% inflation

on an ongoing basis. If this were to happen, it would be harder to achieve the

medium term inflation goal. So we need to guard against this possibility.

He is also required to aim for full employment[10].

He told the business audience that while for some years the bank and others had thought full employment meant an unemployment rate of 5%, the absence of inflation at 5% and the persistence of underemployment (where people wanted more hours) meant it could and should go lower.

Our judgement now is that we can do better than this – that we can sustain an

unemployment rate of 4 point something.

Lower interest rates should help by making it easier to businesses to borrow to expand, and giving consumers something in their pockets to buy from them.

If you don’t succeed…

If that doesn’t happen, the bank will cut again.

Tuesday’s statement as good as said so:

The board will continue to monitor developments in the labour market closely and adjust monetary policy to support sustainable growth in the economy and the achievement of the inflation target over time.

Tuesday’s cut and the next will take the bank into uncharted waters, where its so-called cash rate – what it pays to banks to deposit money with it overnight – is close to zero.

As far as can be discerned it has never been that low in the 100+ years the Reserve Bank has been in operation, originally as the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

Reserve Bank cash rate since 1990

Reserve Bank of Australia[11]

Should inflation still not pick up and employment still not fall as far as it believes it could, it will have to effectively cut its cash rate below zero, forcing cash into the hands of banks by aggressively buying government bonds, giving them little choice but to lend it to households and businesses, in a process known as quantitative easing. It has been done in the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom and Japan, and is by now anything but unconventional[12].

Governor Lowe would prefer the government to pull its weight by cutting tax and boosting spending, especially on infrastructure, and by policies that make Australia more productive.

He said so on Tuesday night

the best approach to delivering lower unemployment and a stronger economy is through structural policies that support firms expanding, investing, innovating and employing people. As we ease monetary policy, it is in the country’s interest that other policy options are considered too.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg gets it.

He pointed out on Tuesday that the yet-to-be-approved tax offsets in the budget will give Australians on up to $126,000 a cash bonus of up to $1,080 when they submit this year’s tax return, far more than the rate cut.

His biggest concern, and the biggest concern of the governor, might be that they don’t spend it. Another concern would be that the banks don’t pass the rate cut on.

The ANZ has said it will only cut mortgage rates by 0.18 points instead of the full 0.25, a decision Frydenberg said “let down” customers. Westpac has cut by only 0.20 points. The National Australia and Commonwealth banks have passed on the cut in full.

On Tuesday night in Sydney Governor Lowe addressed the question of whether the banks should have passed on the full cut head on:

My usual practice in answering this question has been to explain that there are a

range of other factors that influence mortgage pricing, and then say “it all depends”.

Today, though, I would like to break with my usual practice and provide a clearer

answer. And that is: Yes. There has been a substantial reduction in the cost of banks raising funds in wholesale markets. Average rates on retail deposits have also come down.

This means that the lower cash rate should be fully passed through into standard variable mortgage rates. Full pass-through would also mean that the economy receives the full benefit of today’s policy decision.

The Governor is concerned that, for their own reasons, lenders such as ANZ and Westpac are forcing him to cut rates lower than he should and making an already difficult job harder.

If he has to cut further he will, but with the cash rate at just 1.25%, he would dearly love not to have to.

Reserve Bank of Australia[11]

Should inflation still not pick up and employment still not fall as far as it believes it could, it will have to effectively cut its cash rate below zero, forcing cash into the hands of banks by aggressively buying government bonds, giving them little choice but to lend it to households and businesses, in a process known as quantitative easing. It has been done in the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom and Japan, and is by now anything but unconventional[12].

Governor Lowe would prefer the government to pull its weight by cutting tax and boosting spending, especially on infrastructure, and by policies that make Australia more productive.

He said so on Tuesday night

the best approach to delivering lower unemployment and a stronger economy is through structural policies that support firms expanding, investing, innovating and employing people. As we ease monetary policy, it is in the country’s interest that other policy options are considered too.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg gets it.

He pointed out on Tuesday that the yet-to-be-approved tax offsets in the budget will give Australians on up to $126,000 a cash bonus of up to $1,080 when they submit this year’s tax return, far more than the rate cut.

His biggest concern, and the biggest concern of the governor, might be that they don’t spend it. Another concern would be that the banks don’t pass the rate cut on.

The ANZ has said it will only cut mortgage rates by 0.18 points instead of the full 0.25, a decision Frydenberg said “let down” customers. Westpac has cut by only 0.20 points. The National Australia and Commonwealth banks have passed on the cut in full.

On Tuesday night in Sydney Governor Lowe addressed the question of whether the banks should have passed on the full cut head on:

My usual practice in answering this question has been to explain that there are a

range of other factors that influence mortgage pricing, and then say “it all depends”.

Today, though, I would like to break with my usual practice and provide a clearer

answer. And that is: Yes. There has been a substantial reduction in the cost of banks raising funds in wholesale markets. Average rates on retail deposits have also come down.

This means that the lower cash rate should be fully passed through into standard variable mortgage rates. Full pass-through would also mean that the economy receives the full benefit of today’s policy decision.

The Governor is concerned that, for their own reasons, lenders such as ANZ and Westpac are forcing him to cut rates lower than he should and making an already difficult job harder.

If he has to cut further he will, but with the cash rate at just 1.25%, he would dearly love not to have to.

Reserve Bank of Australia[13]

Read more:

Cutting interest rates is just the start. It's about to become much, much easier to borrow[14]

Reserve Bank of Australia[13]

Read more:

Cutting interest rates is just the start. It's about to become much, much easier to borrow[14]

References

- ^ Australian National Accounts (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ 0.3% and 0.2% (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ 2.75% (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ 2.25% (budget.gov.au)

- ^ Australian National Accounts (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ announcing the rates decision (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ not for everybody (theconversation.com)

- ^ 2% and 3% (rba.gov.au)

- ^ Reserve Bank of Australia (rba.gov.au)

- ^ aim for full employment (rba.gov.au)

- ^ Reserve Bank of Australia (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ anything but unconventional (www.bankofengland.co.uk)

- ^ Reserve Bank of Australia (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ Cutting interest rates is just the start. It's about to become much, much easier to borrow (theconversation.com)

Authors: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University