Labor and Coalition proposals side by side

- Written by Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute

The two major parties have kicked off the election campaign with very different policies for cuts to personal income tax.

The Coalition promises its tax plan will deliver “lower, simpler, fairer taxes[1]” while Labor says its plan is all about the “fair go[2]”.

But putting aside the spin, how do the promised tax cuts compare? Will they make the tax system more progressive, or less? And what do they mean for the budget bottom line?

Tasting each plan

The Coalition plan comes in three stages.

The major part of Stage 1 is the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (the LMITO, or “lamington” as some are calling it), which gives everyone earning less than A$126,000 a cheque in the mail come July and then another one in each of the following three years.

Stage 2 (2022-23) will lift the thresholds of the 19% and the 32.5% brackets.

The biggest cuts come in stage 3 (2024-25) when the 32.5% tax rate is cut to 30% and the 37% bracket is removed entirely.

The effect would be that everyone earning between $45,000 and $200,000 would face the same 30% marginal tax rate from July 1, 2024.

Read more: A simpler tax system should spark joy. Sadly, the one in this budget doesn’t[3]

The Labor plan gives a slightly higher offset (up to $95 a year more) for people earning less than $48,000 and then matches the lamington for people earning $48,000 or more.

Under Labor the lamington will be permanent, but Labor will not proceed with stages 2 and 3 of the Coalition’s tax plan.

From July 1, 2019, Labor will also increase the top marginal tax rate paid on incomes above $180,000 from 45% to 47% for an unspecified time, making it essentially a return of the Abbott government’s “temporary deficit reduction levy”.

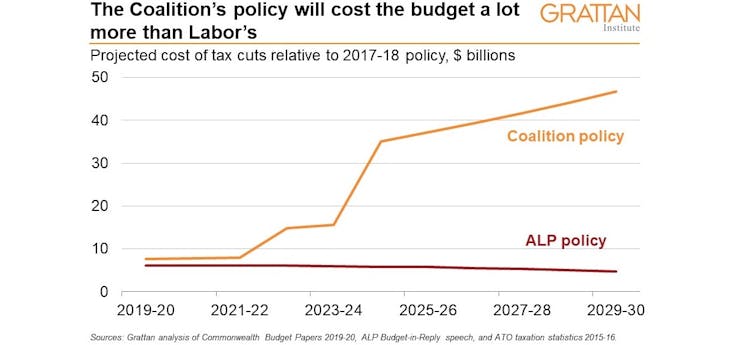

The Coalition’s plan will cost the budget about A$298 billion over the next decade. Labor’s plan is at the moment much cheaper at about A$63 billion over the same period.

Who wins, who loses?

How will different taxpayers fare under the two plans? That depends on what point in time we compare them.

If we focus on the next three years, there will be no difference in tax under the two plans for most people. The lowest income earners won’t pay income tax under either party’s policy.

About a quarter of taxpayers with taxable incomes of between $22,000 and $48,000 will be up to $95 better off under the Labor plan.

At the other end of the income spectrum, the top 5% of taxpayers earning more than $180,000 will pay more under Labor (equivalent to about $400 additional tax for someone earning $200,000).

The big differences between Labor and the Coalition’s tax policies open up when we get to stage 2 (2022-23) and particularly stage 3 (2024-25) of the Coalition’s plan.

Read more:

A simpler tax system should spark joy. Sadly, the one in this budget doesn’t[4]

By the end of the next decade, assuming both parties make no further changes to income tax policy:

• The third of taxfilers earning up to $40,000 will pay no tax or be slightly better off under Labor’s plan because Labor retains the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset.

• The third of taxfilers earning $40,000-$90,000 will be a bit better off under the Coalition’s plan. A taxpayer in the middle of the income distribution, earning $63,000 a year by 2029-30, will be approximately $432 a year better off under the Coalition.

• The third of taxfilers earning more than $90,000 will be at least $1,000 better off under the Coalition, and people in the top 8% will be over $10,000 better off.

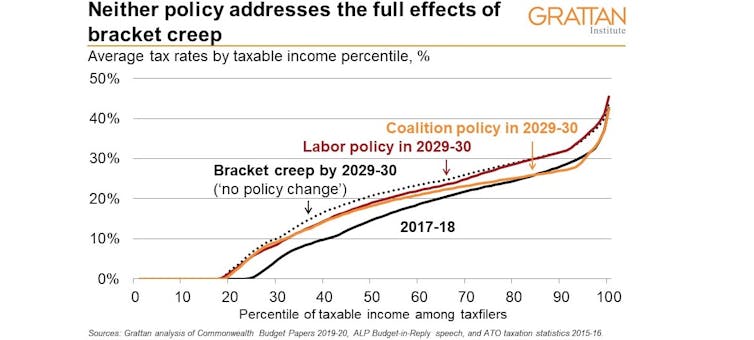

The Coalition would refund bracket creep only at the top

The top 15% of earners would be fully compensated for bracket creep under the Coalition’s plan, paying the same average tax rate or less in 2029-30 as they do today.

But middle income earners would still face higher average tax rates than today.

If Labor were to make no further changes to income tax policy over the decade, Labor’s plan would see around 80% of taxpayers facing higher average tax rates in 2029-30 than at present. Top income earners would receive almost no insulation from bracket creep. This is why Labor’s plan results in a much healthier bottom line.

But it is difficult to imagine that any government could resist offering tax cuts to compensate for the effects of bracket creep over such an extended period.

Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen has already indicated that a future Labor government would consider tax cuts on a budget-by-budget basis[5], meaning that today’s policy doesn’t necessarily tell us what policy will be in a decade’s time.

Who wins, who loses?

How will different taxpayers fare under the two plans? That depends on what point in time we compare them.

If we focus on the next three years, there will be no difference in tax under the two plans for most people. The lowest income earners won’t pay income tax under either party’s policy.

About a quarter of taxpayers with taxable incomes of between $22,000 and $48,000 will be up to $95 better off under the Labor plan.

At the other end of the income spectrum, the top 5% of taxpayers earning more than $180,000 will pay more under Labor (equivalent to about $400 additional tax for someone earning $200,000).

The big differences between Labor and the Coalition’s tax policies open up when we get to stage 2 (2022-23) and particularly stage 3 (2024-25) of the Coalition’s plan.

Read more:

A simpler tax system should spark joy. Sadly, the one in this budget doesn’t[4]

By the end of the next decade, assuming both parties make no further changes to income tax policy:

• The third of taxfilers earning up to $40,000 will pay no tax or be slightly better off under Labor’s plan because Labor retains the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset.

• The third of taxfilers earning $40,000-$90,000 will be a bit better off under the Coalition’s plan. A taxpayer in the middle of the income distribution, earning $63,000 a year by 2029-30, will be approximately $432 a year better off under the Coalition.

• The third of taxfilers earning more than $90,000 will be at least $1,000 better off under the Coalition, and people in the top 8% will be over $10,000 better off.

The Coalition would refund bracket creep only at the top

The top 15% of earners would be fully compensated for bracket creep under the Coalition’s plan, paying the same average tax rate or less in 2029-30 as they do today.

But middle income earners would still face higher average tax rates than today.

If Labor were to make no further changes to income tax policy over the decade, Labor’s plan would see around 80% of taxpayers facing higher average tax rates in 2029-30 than at present. Top income earners would receive almost no insulation from bracket creep. This is why Labor’s plan results in a much healthier bottom line.

But it is difficult to imagine that any government could resist offering tax cuts to compensate for the effects of bracket creep over such an extended period.

Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen has already indicated that a future Labor government would consider tax cuts on a budget-by-budget basis[5], meaning that today’s policy doesn’t necessarily tell us what policy will be in a decade’s time.

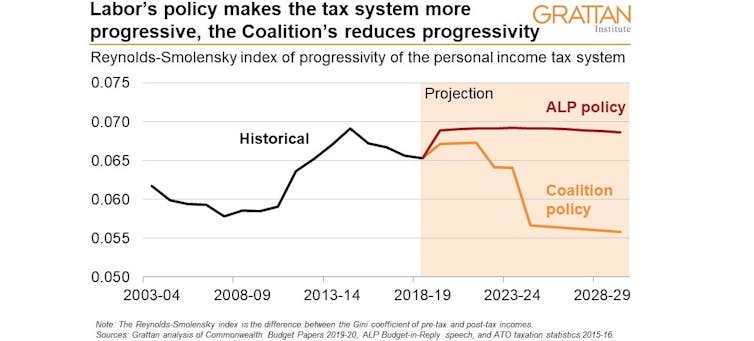

The Coalition would make the system less progressive

The “progressivity” of a tax system — the degree to which it reduces income inequality — can be measured by the Reynolds-Smolensky Index[6]. It shows the tax system will at first become more progressive under both parties’ policies — meaning that post-tax income will become more equally shared.

This is because of the boost to the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset. But the final two rounds of tax cuts, at this stage offered only by the Coalition, will make the system significantly less progressive as the benefit is concentrated among higher income earners.

What Labor is offering at the moment will make the system more progressive and only becomes slightly less so over time.

The Coalition would make the system less progressive

The “progressivity” of a tax system — the degree to which it reduces income inequality — can be measured by the Reynolds-Smolensky Index[6]. It shows the tax system will at first become more progressive under both parties’ policies — meaning that post-tax income will become more equally shared.

This is because of the boost to the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset. But the final two rounds of tax cuts, at this stage offered only by the Coalition, will make the system significantly less progressive as the benefit is concentrated among higher income earners.

What Labor is offering at the moment will make the system more progressive and only becomes slightly less so over time.

But both sides are virtue signalling

Despite the hype, the personal income tax system will look pretty similar for the next three years regardless of which party wins office.

Labor will tax high income earners more and low income earners slightly less. But for around 70% of people, personal income tax rates will be identical in three years time whether Scott Morrison or Bill Shorten is prime minister.

The big differences lie in the distant future, beyond 2024-25. Since it is almost unimaginable that either side of politics would leave its tax policies unchanged through another two elections the differences in the announced plans have more to do with signaling philosophy than reality.

The Coalition’s philosophy is about restraining tax as a share of the economy, even if that means it will need to shrink government spending as a share of GDP (in ways that are not yet unexplained[7]).

Labor is signalling that it is more comfortable with the tax share creeping up — mostly thanks to increased contributions from high income earners — but it will make sure lower income earners don’t end up worse off.

Who says elections aren’t a contest of ideas?

Read more:

Potentially unaffordable, and it still won't fix bracket creep. The Coalition's $300 billion tax plan assessed[8]

But both sides are virtue signalling

Despite the hype, the personal income tax system will look pretty similar for the next three years regardless of which party wins office.

Labor will tax high income earners more and low income earners slightly less. But for around 70% of people, personal income tax rates will be identical in three years time whether Scott Morrison or Bill Shorten is prime minister.

The big differences lie in the distant future, beyond 2024-25. Since it is almost unimaginable that either side of politics would leave its tax policies unchanged through another two elections the differences in the announced plans have more to do with signaling philosophy than reality.

The Coalition’s philosophy is about restraining tax as a share of the economy, even if that means it will need to shrink government spending as a share of GDP (in ways that are not yet unexplained[7]).

Labor is signalling that it is more comfortable with the tax share creeping up — mostly thanks to increased contributions from high income earners — but it will make sure lower income earners don’t end up worse off.

Who says elections aren’t a contest of ideas?

Read more:

Potentially unaffordable, and it still won't fix bracket creep. The Coalition's $300 billion tax plan assessed[8]

References

- ^ lower, simpler, fairer taxes (www.budget.gov.au)

- ^ fair go (www.billshorten.com.au)

- ^ A simpler tax system should spark joy. Sadly, the one in this budget doesn’t (theconversation.com)

- ^ A simpler tax system should spark joy. Sadly, the one in this budget doesn’t (theconversation.com)

- ^ consider tax cuts on a budget-by-budget basis (www.afr.com)

- ^ Reynolds-Smolensky Index (www.cgdev.org)

- ^ that are not yet unexplained (www.afr.com)

- ^ Potentially unaffordable, and it still won't fix bracket creep. The Coalition's $300 billion tax plan assessed (theconversation.com)

Authors: Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute