Depending on who you are, the benefits of a cashless society are greatly overrated

- Written by Steve Worthington, Adjunct Professor, Swinburne University of Technology

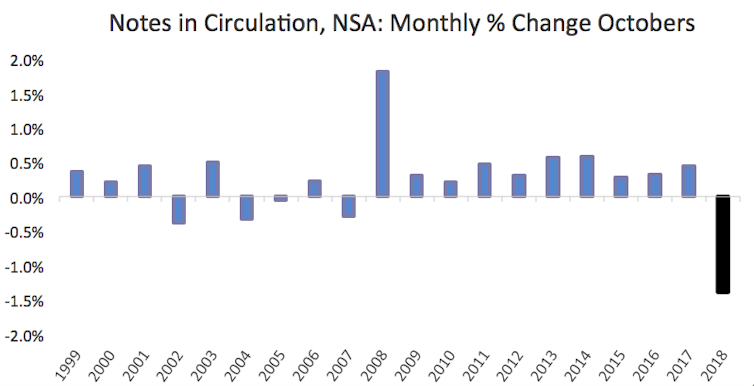

After recreational cannabis use became legal in Canada last October, research shows the number of bank notes in circulation[1] fell sharply. Before, marijuana buyers used cash to keep their transactions anonymous. After, there was a massive switch to the convenience of cashless payments.

The fall in October was particularly large and contrasts with average monthly gains of 0.4 per cent over the previous five years.

Bank of Canada[2]

The fall in October was particularly large and contrasts with average monthly gains of 0.4 per cent over the previous five years.

Bank of Canada[2]

It’s a prime example of what makes a cashless society so attractive to law makers and enforcers wanting to put the squeeze on the “black economy” that can’t be tracked or taxed.

But not everyone clinging to cash has illicit motivations.

This month Philadelphia became the first major US city requiring all merchants to accept cash. This week the state of New Jersey followed suit. Other US cities and states are considering the same.

The chief concern is that cashless payment systems discriminate against the “unbanked”[3] – those without a bank account – making life harder for those already on the margins. “It’s really a fairness issue,” said the councillor who sponsored the ban[4]. “Equal access is what we’re trying to get.”

So as nations make plans to become cashless societies, and automated teller machines start to go the way of telephone booths, it’s timely to consider the pros and cons of cashless payments. We need ensure our enthusiastic march to the future[5] does not trample over people or leave them behind.

Counting the unbanked

A national survey[6] by the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation shows about 8.4 million US households – or 6.5% of all households – were unbanked in 2017. Philadelphia’s new law is primarily to protect such people.

Taking effect on July 1, the law requires most stores to accept cash, and forbids them charging a surcharge for paying with cash. New York, Washington and Chicago are among the cities investigating similar measures.

Read more: Why cash remains sacred in American churches[7]

In Britain a review of cash accessibility[8] headed by former chief financial ombudsman Natalie Ceeney has urged financial regulators to stop the country “sleepwalking[9]” into a cashless society. Its report, published this month, recommends a national guarantee that consumers will be able to access and use cash for as long as they need it.

About 17% of the British population – over 8 million adults – would struggle to cope in a cashless society, the report says: “While most of society recognises the benefits of digital payments, our research shows the technology doesn’t yet work for everyone.”

The tip of the iceberg is the decline in bank branches and ATMs. Two-thirds of bank branches have closed in the past three decades[10], and the rate of closure in accelerating. Cashpoints are disappearing at a rate of nearly 500 a month[11].

Learning from Sweden

But this is simply the most obvious symptom, according to the Ceeney report, with evidence from other countries demonstrating the issue of merchants accepting cash is more important.

“Sweden, the most cashless society in the world, outlines the dangers of sleepwalking into a cashless society: millions of people could potentially be left out of the economy,” it says, “and face increased risks of isolation, exploitation, debt and rising costs.”

About 85% of transactions in Sweden are now digital. Half the nation’s retailers expect to stop accepting cash before 2025.

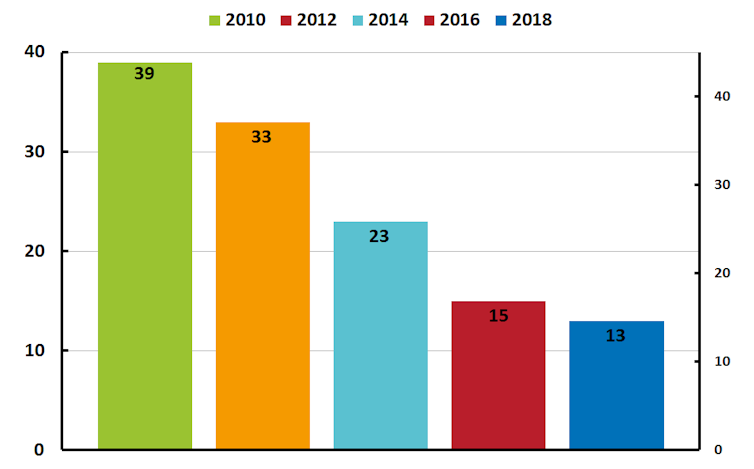

Percentage of Swedes that used cash for their most recent purchase.

The Riksbank[12]

Percentage of Swedes that used cash for their most recent purchase.

The Riksbank[12]

The nation is now counting the societal costs.

The Riksbank, Sweden’s Central Bank, is asking all banks to keep providing and accepting cash while government works out how best to protect those who most rely on cash[13] – such as those aged 65 or more, those living in rural areas, those with disabilities and recent immigrants.

An estimated 1 million Swedes are not comfortable with using a computer or smart phone to do their banking. Immigrants often do not have a bank account or credit history to get a payment card.

Considering consequences

“If cash disappears that would be a big change, with major implications for society and the economy,” Mats Dillen, the head of the Swedish Parliament Committee studying the issue, has said[14]. “We need to pause and think about whether this is good or bad and not just sit back and let it happen.”

The New York City Council member pushing the bill to ban cashless-only stores, Ritchie Torres, agrees. He is particularly concerned about the issues of class and ethnic discrimination.

“I started coming across coffee shops and cafés that were exclusively cashless and I thought: but what if I was a low-income New Yorker who has no access to a card?” Ritchie Torres has explained[15]. “I thought about it more and realised that even if a policy seems neutral in theory it can be racially exclusionary in practice.

Read more: Why a 'cashless' society would hurt the poor: A lesson from India[16]

"In some ways making a payment card a requirement for consumption is analogous to making identification a requirement for voting. The effect is the same: it disempowers communities of colour.”

These are timely reminders that we should never assume that technological change is value-free, or necessarily an improvement. All revolutions have their hidden costs. We need to ensure those costs are shared equitably, and that no one is accidentally disadvantaged by them.

References

- ^ bank notes in circulation (blogs.lse.ac.uk)

- ^ Bank of Canada (blogs.lse.ac.uk)

- ^ against the “unbanked” (www.wsj.com)

- ^ councillor who sponsored the ban (www.phillyvoice.com)

- ^ march to the future (theconversation.com)

- ^ national survey (economicinclusion.gov)

- ^ Why cash remains sacred in American churches (theconversation.com)

- ^ review of cash accessibility (www.accesstocash.org.uk)

- ^ sleepwalking (www.finextra.com)

- ^ in the past three decades (www.ft.com)

- ^ a rate of nearly 500 a month (www.finextra.com)

- ^ The Riksbank (www.riksbank.se)

- ^ who most rely on cash (www.riksbank.se)

- ^ has said (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Ritchie Torres has explained (www.grubstreet.com)

- ^ Why a 'cashless' society would hurt the poor: A lesson from India (theconversation.com)

Authors: Steve Worthington, Adjunct Professor, Swinburne University of Technology