Dentists need a licence to practice. Why not economists?

- Written by Ross Guest, Professor of Economics and National Senior Teaching Fellow, Griffith University

The great British economist John Maynard Keynes said he longed for the day when economics could be thought of as a “matter for specialists - like dentistry[1]”.

It’s easier to become an economist than a dentist, or a doctor or a lawyer. For those and other professions you need to be accredited - you need a licence to practice.

The economics profession requires nothing other than a university degree, and this month in its regular poll of 54 leading economists, the Economic Society of Australia asked[2] whether it should set the bar higher.

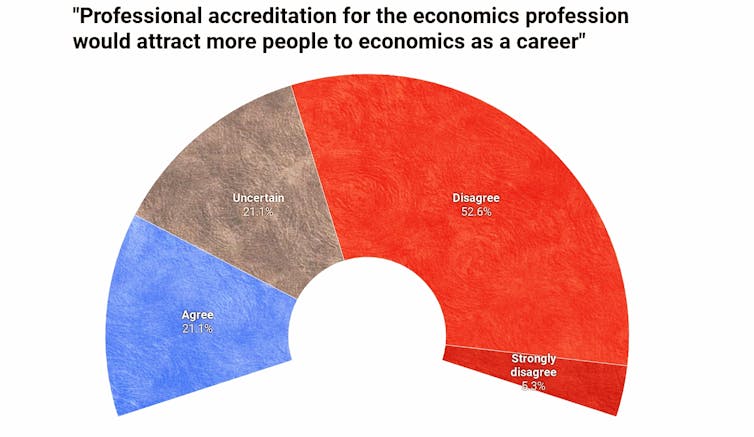

The first question asked whether:

…professional accreditation for the economics profession would attract more people to economics as a career.

Certainly, fewer people are being attracted.

Last year, in a speech titled What Happened to the Study of Economics?[3], Reserve Bank official Jacqui Dwyer lamented the dramatic drop in NSW Year 12 economics enrolments, from about 20,000 in the early 1990s to about 5,000 today – many of them displaced by business studies enrolments.

An image problem or an identity problem?

It is a similarly grim picture at universities. Economics is being displaced by business-oriented subjects and has a declining share of the student population. From 2001 to 2016, enrolments in economics have flatlined (declining by less than 1%) while total university enrolments have climbed more than 3%.

Also worrying is the widening gender gap. In the early 1990s there were roughly even shares of male and female economics students in high schools. Now there are roughly twice as many men as women – a wider gap than science, technology, engineering and mathematics, and a much wider gap than in business studies.

Students from low socio-economic backgrounds are abandoning economics in droves. In the early 1990s about 25% of high school economics students were from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Today it is nearer 12%.

Read more: Economics needs to get real if we want more young Australians to study it[4]

The puzzle is that the job market for economists remains robust.

As Dwyer notes, graduate salaries are higher for students with economics degrees than for general business qualifications, and employment rates are about the same. Dwyer concludes that “economics has an image problem: too few students understand what economics is and how it is relevant to them”.

But it might also have an identity problem.

Economics graduates are less likely than some other types of graduates to be employed in their field of specialisation (a point made by Dwyer). Their skills are generally useful.

Of our regular panel of 54 leading economists[5], 19 responded to the poll.

Of these, 11 (58%) either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the proposition that accreditation would attract more people to economics as a career.

Economic Society of Australia March 2019 poll[6]

Lisa Cameron from Monash University said the problem with economics was not the career path, but its image:

Economics brings up images of boring, middle-aged white men in grey suits who think they have all the answers. For many students this is a real turn-off.

Female students, for example, often come to me and express that they can’t see how they can fit into this scene, and whether it would even be worth trying. I find it quite discouraging myself.

An alternative to professional certification suggested by Gigi Foster of the University of NSW was curriculum certification, where the Economic Society of Australia would be contracted to set up and run a system of certification for tertiary curricula based on the Economics Learning Standards[7] it has already developed.

This focus on the curriculum rather than career identity was endorsed by Fabrizio Carmignani of Griffith University, who argued that the key to attracting more people to economics was:

…our ability as economists to explain to the community, employers, and general public what we do and why; in our ability to show that the skills and logic acquired through studying economics can be applied to a large variety of professions and industries.

Another problem with accreditation would be what to accredit. Melbourne University’s John Freebairn asked:

Suppose we go to the three-year undergraduate degrees in economics, business and commerce – what would be the accreditation line; how many subjects at level three, and then the minimum of core micro-, macro- and econometrics subjects, or electives? Any accreditation measure will be arbitrary, and provide limited if any additional information to potential employers.

Peter Abelson pointed out it had been discussed several times before when he was Secretary of the Society between 1993 and 2006.

There was always quite firm opposition to accreditation. The neo-liberal view was that the market should decide who are economists and who not. The pragmatic opposition was that there is no simple test of who is an economist.

Macquarie University’s Geoffrey Kingston paraphrased the title of a song by The Smiths. He said economists “just hadn’t earned it yet[8]”.

Accreditation needs to await more scientific heft and professional agreement on our part. The day will come when we can put up our hands and demand accreditation.

Would it be worth it?

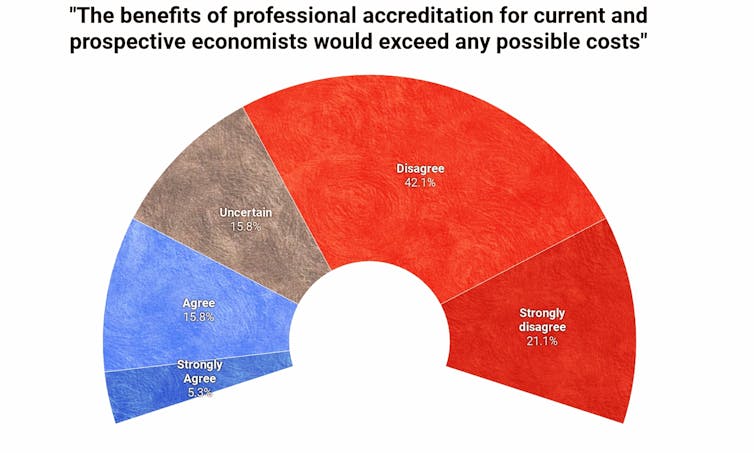

The second question was whether the benefits of accreditation would exceed the possible costs.

Opinions divided along the same lines. Those opposed to accreditation (the majority) believed that the costs would outweigh the benefits.

Economic Society of Australia March 2019 poll[6]

Lisa Cameron from Monash University said the problem with economics was not the career path, but its image:

Economics brings up images of boring, middle-aged white men in grey suits who think they have all the answers. For many students this is a real turn-off.

Female students, for example, often come to me and express that they can’t see how they can fit into this scene, and whether it would even be worth trying. I find it quite discouraging myself.

An alternative to professional certification suggested by Gigi Foster of the University of NSW was curriculum certification, where the Economic Society of Australia would be contracted to set up and run a system of certification for tertiary curricula based on the Economics Learning Standards[7] it has already developed.

This focus on the curriculum rather than career identity was endorsed by Fabrizio Carmignani of Griffith University, who argued that the key to attracting more people to economics was:

…our ability as economists to explain to the community, employers, and general public what we do and why; in our ability to show that the skills and logic acquired through studying economics can be applied to a large variety of professions and industries.

Another problem with accreditation would be what to accredit. Melbourne University’s John Freebairn asked:

Suppose we go to the three-year undergraduate degrees in economics, business and commerce – what would be the accreditation line; how many subjects at level three, and then the minimum of core micro-, macro- and econometrics subjects, or electives? Any accreditation measure will be arbitrary, and provide limited if any additional information to potential employers.

Peter Abelson pointed out it had been discussed several times before when he was Secretary of the Society between 1993 and 2006.

There was always quite firm opposition to accreditation. The neo-liberal view was that the market should decide who are economists and who not. The pragmatic opposition was that there is no simple test of who is an economist.

Macquarie University’s Geoffrey Kingston paraphrased the title of a song by The Smiths. He said economists “just hadn’t earned it yet[8]”.

Accreditation needs to await more scientific heft and professional agreement on our part. The day will come when we can put up our hands and demand accreditation.

Would it be worth it?

The second question was whether the benefits of accreditation would exceed the possible costs.

Opinions divided along the same lines. Those opposed to accreditation (the majority) believed that the costs would outweigh the benefits.

Economic Society of Australia March 2019 poll[9]

As to my own views, first a declaration: under the auspices of the former Office for Learning and Teaching, the Economics Society of Australia and the Australian Business Deans Council, I chaired the working group that developed the Economics Learning Standards[10] to which Gigi Foster referred (and Foster was a member of the group).

I fear that many who rejected the notion of accreditation would also reject the notion of learning standards.

My response would be that many disciplines have recognised the need for stakeholders in professional education to have a shared understanding of what is taught. Those stakeholders include employers, governments, taxpayers, prospective students (international and domestic), and their parents.

I feel the same way about professional accreditation: it is about quality assurance.

That said, I acknowledge that the bureaucratic compliance costs in such a process are an irritant at the very least, so they would need to be kept at a minimum, which draws me to the suggestions of a couple of respondents that when the time is right, the Economics Society of Australia can play a lead role in the professional accreditation of economists.

Read more:

Why women in economics have little to celebrate[11]

Economic Society of Australia March 2019 poll[9]

As to my own views, first a declaration: under the auspices of the former Office for Learning and Teaching, the Economics Society of Australia and the Australian Business Deans Council, I chaired the working group that developed the Economics Learning Standards[10] to which Gigi Foster referred (and Foster was a member of the group).

I fear that many who rejected the notion of accreditation would also reject the notion of learning standards.

My response would be that many disciplines have recognised the need for stakeholders in professional education to have a shared understanding of what is taught. Those stakeholders include employers, governments, taxpayers, prospective students (international and domestic), and their parents.

I feel the same way about professional accreditation: it is about quality assurance.

That said, I acknowledge that the bureaucratic compliance costs in such a process are an irritant at the very least, so they would need to be kept at a minimum, which draws me to the suggestions of a couple of respondents that when the time is right, the Economics Society of Australia can play a lead role in the professional accreditation of economists.

Read more:

Why women in economics have little to celebrate[11]

References

- ^ like dentistry (goo.gl)

- ^ asked (esacentral.org.au)

- ^ What Happened to the Study of Economics? (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ Economics needs to get real if we want more young Australians to study it (theconversation.com)

- ^ 54 leading economists (esacentral.org.au)

- ^ Economic Society of Australia March 2019 poll (esacentral.org.au)

- ^ Economics Learning Standards (www.economicslearningstandards.com)

- ^ just hadn’t earned it yet (www.youtube.com)

- ^ Economic Society of Australia March 2019 poll (esacentral.org.au)

- ^ Economics Learning Standards (www.economicslearningstandards.com)

- ^ Why women in economics have little to celebrate (theconversation.com)

Authors: Ross Guest, Professor of Economics and National Senior Teaching Fellow, Griffith University

Read more http://theconversation.com/dentists-need-a-licence-to-practice-why-not-economists-113380