Fairness isn't optional. How to design a tax system that works

- Written by Fabrizio Carmignani, Professor, Griffith Business School, Griffith University

This is part of a major series called Advancing Australia, in which leading academics examine the key issues facing Australia in the lead-up to the 2019 federal election and beyond. Read the other pieces in the series here[1].

Any discussion of the tax system requires a common understanding that its purpose goes beyond revenue.

To see this, ask whether we would be willing to raise as much revenue as we do now by simply requiring each resident and business to pay A$16,400 a year, with no further complications.

We could do this. It would generate the A$450 billion the Commonwealth raises now.

And it would be appealing in some ways. It would minimise tax evasion. There would be no exemptions, no tax returns, no loopholes. And payment would be easy to monitor. It would also save the taxpayer the cost of submitting tax returns and the government the cost of checking them.

We all want some fairness

People who earn more than A$76,000 would be delighted, because they would pay less tax than they do now.

Households with people who earn much less would be less happy. Each child, no matter how young, would have to pay A$16,400. A household with two parents (one working) and one child would have to pay twice as much as it does now.

Unemployed Australians would pay the same as mining tycoons. Mum-and-dad businesses would pay the same as large corporations.

But we wouldn’t accept such a system, because it wouldn’t be fair. And that’s not just because fairness is one of our core values.

Inequality has an economic cost. Modelling by staff of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) shows that a 1% increase in a nation’s inequality lowers its gross domestic product by between 0.6% and 1.1%[2].

The researchers find that beyond a certain point growing inequality can undermine the foundations of market economies and lead to inequalities of opportunity. They report[3]:

This smothers social mobility, and weakens incentives to invest in knowledge. The result is a misallocation of skills, and even waste through more unemployment, ultimately undermining efficiency and growth potential.

Progressivity helps

Almost all developed countries use the tax system to fight inequality, by increasing the rate of personal income tax as taxable income grows. In a typical “progressive” personal income tax system the first $5000 earned might be taxed at ten cents in the dollar, while subsequent earnings might be taxed at 20 cents in the dollar. The result is that higher earners pay a greater proportion of their earnings in tax.

Australia has such a system. Our personal income tax system is more progressive than most of the 36 OECD members[4].

But it has been getting less progressive over time.

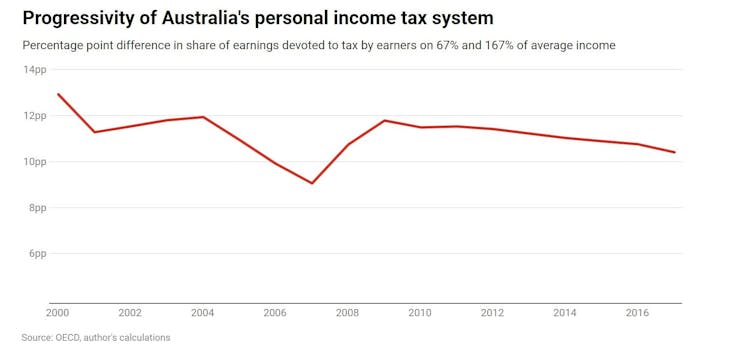

A standard measure is the difference in proportion of earnings devoted to tax (the “tax wedge”) for high earners on 167% of a nation’s average income and low earners on 67% of the average. The greater the difference, the more progressive the system.

The graph shows Australia’s system became less progressive throughout the first mining boom in the 2000s. It then became more progressive during the global financial crisis and probably as a result of the government’s response to it. Progressivity has been drifting down since.

Unless we take action to make our personal income tax system more progressive, it is likely to become less progressive still.

Tax cuts legislated in 2018 will accentuate the trend by dramatically flattening Australia’s personal income tax scales by 2024-25, unless reversed as Labor has promised should it win the election[5].

Our company tax rate is high …

Company taxes are almost always proportional, set at a flat rate. Debate is about how high that rate should be.

Lower rates are said to encourage business investment, stimulating employment, wages and economic growth. But if company taxes are cut, government needs to find more revenue from somewhere else, or wind back spending.

Read more:

New figures put it beyond doubt. When it comes to company tax, we are a high-tax country, in part because it works well for us[6]

Australia’s standard rate is 30%, reduced to 26.5% (and soon enough 25%) for companies with turnovers of less than A$50 million. It is the second-highest rate in the OECD, behind only France. A broader measure of Australia’s “effective” company tax rate, taking into account tax breaks, still shows it is high compared to other countries.

The high rate is little noticed at home. Most Australian shareholders are able to get a tax credit for the company tax paid on the profit that funds their dividend (a practice Labor has promised to wind back[7]). This means the credit can cut the the income tax collected from a dividend recipient to zero, but not below it resulting in a payment from the Tax Office.

… which may not be a problem

There is no clear association between corporate tax cuts and economic growth.

Rough calculations using OECD and International Monetary Fund data suggest that, if anything, higher economic growth is associated with smaller tax cuts.

In part this is because foreign companies consider things other than the tax rate in deciding where to invest. In part it is because the revenue lost from corporate tax cuts has to be made up from somewhere else (most likely from extra income tax as incomes rise and push people into higher tax brackets).

Since 2001, when Australia’s rate of company tax was cut to 30%, Australia’s annual economic growth rate has averaged 2.9%. In the 17 years before then, when the company tax rate averaged about 39%, annual economic growth averaged 3.5%.

None of this implies causality. But it does show that lower company tax rates and better economic performance do not necessarily go together.

International surveys[8] show that Australia, despite its relatively high company tax rate, is regarded as one of the 20 countries in which doing business is easiest. What most works against Australia is the high costs of electricity.

New taxes are waiting in the wings

In summary, there appears to be scope for reducing personal income tax rates at the lower end of income distribution while increasing them at the top end.

Our company tax rates are high, but this need not be a problem.

If company taxes were to be cut, other taxes would have to increase. One option is to increase the goods and services tax. But this is not ideal as the GST is a regressive tax; that is, it tends to make income distribution more unequal.

There are other options.

We could impose an extra, much higher tax rate on very high incomes, as Democratic representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez[9] has proposed for the US.

It wouldn’t be a first. Australia’s top marginal rate was 75% in the early 1950s[10]. Or we could reimpose an inheritance tax. A well-designed one would not only fund government spending but also work against intergenerational inequality.

Read more:

The workplace challenge facing Australia (spoiler alert – it’s not technology)[11]

The graph shows Australia’s system became less progressive throughout the first mining boom in the 2000s. It then became more progressive during the global financial crisis and probably as a result of the government’s response to it. Progressivity has been drifting down since.

Unless we take action to make our personal income tax system more progressive, it is likely to become less progressive still.

Tax cuts legislated in 2018 will accentuate the trend by dramatically flattening Australia’s personal income tax scales by 2024-25, unless reversed as Labor has promised should it win the election[5].

Our company tax rate is high …

Company taxes are almost always proportional, set at a flat rate. Debate is about how high that rate should be.

Lower rates are said to encourage business investment, stimulating employment, wages and economic growth. But if company taxes are cut, government needs to find more revenue from somewhere else, or wind back spending.

Read more:

New figures put it beyond doubt. When it comes to company tax, we are a high-tax country, in part because it works well for us[6]

Australia’s standard rate is 30%, reduced to 26.5% (and soon enough 25%) for companies with turnovers of less than A$50 million. It is the second-highest rate in the OECD, behind only France. A broader measure of Australia’s “effective” company tax rate, taking into account tax breaks, still shows it is high compared to other countries.

The high rate is little noticed at home. Most Australian shareholders are able to get a tax credit for the company tax paid on the profit that funds their dividend (a practice Labor has promised to wind back[7]). This means the credit can cut the the income tax collected from a dividend recipient to zero, but not below it resulting in a payment from the Tax Office.

… which may not be a problem

There is no clear association between corporate tax cuts and economic growth.

Rough calculations using OECD and International Monetary Fund data suggest that, if anything, higher economic growth is associated with smaller tax cuts.

In part this is because foreign companies consider things other than the tax rate in deciding where to invest. In part it is because the revenue lost from corporate tax cuts has to be made up from somewhere else (most likely from extra income tax as incomes rise and push people into higher tax brackets).

Since 2001, when Australia’s rate of company tax was cut to 30%, Australia’s annual economic growth rate has averaged 2.9%. In the 17 years before then, when the company tax rate averaged about 39%, annual economic growth averaged 3.5%.

None of this implies causality. But it does show that lower company tax rates and better economic performance do not necessarily go together.

International surveys[8] show that Australia, despite its relatively high company tax rate, is regarded as one of the 20 countries in which doing business is easiest. What most works against Australia is the high costs of electricity.

New taxes are waiting in the wings

In summary, there appears to be scope for reducing personal income tax rates at the lower end of income distribution while increasing them at the top end.

Our company tax rates are high, but this need not be a problem.

If company taxes were to be cut, other taxes would have to increase. One option is to increase the goods and services tax. But this is not ideal as the GST is a regressive tax; that is, it tends to make income distribution more unequal.

There are other options.

We could impose an extra, much higher tax rate on very high incomes, as Democratic representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez[9] has proposed for the US.

It wouldn’t be a first. Australia’s top marginal rate was 75% in the early 1950s[10]. Or we could reimpose an inheritance tax. A well-designed one would not only fund government spending but also work against intergenerational inequality.

Read more:

The workplace challenge facing Australia (spoiler alert – it’s not technology)[11]

References

- ^ here (theconversation.com)

- ^ by between 0.6% and 1.1% (www.oecd.org)

- ^ report (www.oecd.org)

- ^ 36 OECD members (www.oecd.org)

- ^ promised should it win the election (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ New figures put it beyond doubt. When it comes to company tax, we are a high-tax country, in part because it works well for us (theconversation.com)

- ^ Labor has promised to wind back (www.chrisbowen.net)

- ^ International surveys (www.doingbusiness.org)

- ^ Democratic representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (www.businessinsider.com.au)

- ^ 75% in the early 1950s (archive.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ The workplace challenge facing Australia (spoiler alert – it’s not technology) (theconversation.com)

Authors: Fabrizio Carmignani, Professor, Griffith Business School, Griffith University

Read more http://theconversation.com/fairness-isnt-optional-how-to-design-a-tax-system-that-works-111493