Understanding Hayne. Why less is more

- Written by Elise Bant, Professor of Law, University of Melbourne

One of the most important lessons to come out of last week’s banking royal commission is one of the least likely to grab attention, certainly not in the way the resignation of NAB chair Ken Henry did[1].

It’s that, in the view of Royal Commissioner Kenneth Hayne, when all is said and done the complex patchwork of rules that regulate financial institutions can be boiled down to six simple requirements:

obey the law

do not mislead or deceive

act fairly

provide services that are fit for purpose

deliver services with reasonable care and skill, and

when acting for another, act in their best interests

Yet, under our current law, these six principles are expressed in different terms in multiple pieces of legislation that run to thousands of pages and even more regulations, at both state and federal levels.

The labyrinth is arguably unnavigable for even sophisticated parties with access to good legal advice.

It wholly fails as a way of communicating the law to ordinary people, the businesses and citizens who are bank customers. It also provides an endless supply of “stall and evade” opportunities for wrongdoers who can clog up the courts with technical and strategic debates over how to interpret the labyrinth.

Legislative porridge

Even the best-intentioned plaintiff or prosecutor can end up pleading every possible permutation of the law to try and cover all bases.

The inevitable result is to “delay the proceeding and increase legal expenses[2]”, in the words of a recent Federal Court judgement.

Take the core prohibition of “misleading or deceptive” conduct.

Research conducted at Melbourne Law School finds the same prohibition in slightly different forms, with different requirements, different defences, and different remedies and penalties in more than 30 pieces of state and federal legislation[3].

The result has been described by another Federal Court judge as a “legislative porridge[4]”.

For many Australians it makes the use of the courts to resolve financial disputes with banks and insurance companies simply not possible.

As a result, we have developed a parallel “soft law”, that doesn’t work badly.

The Banking Code of Practice[5] sets out what banks should do and the Financial Complaints Authority[6] resolves disputes.

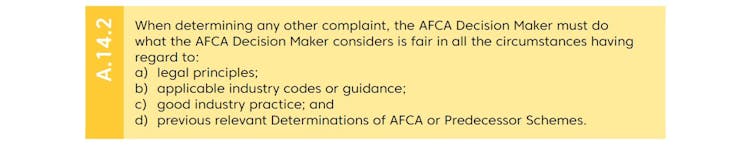

The Authority’s guiding principle is as simple as could be – that its decision be fair in all the circumstances[7].

Australian Financial Complaints Authority Operational Guidelines[8]

It raises the question of why the law needs to be so complex when the alternative to it doesn’t need to be.

Simplification has to start somewhere

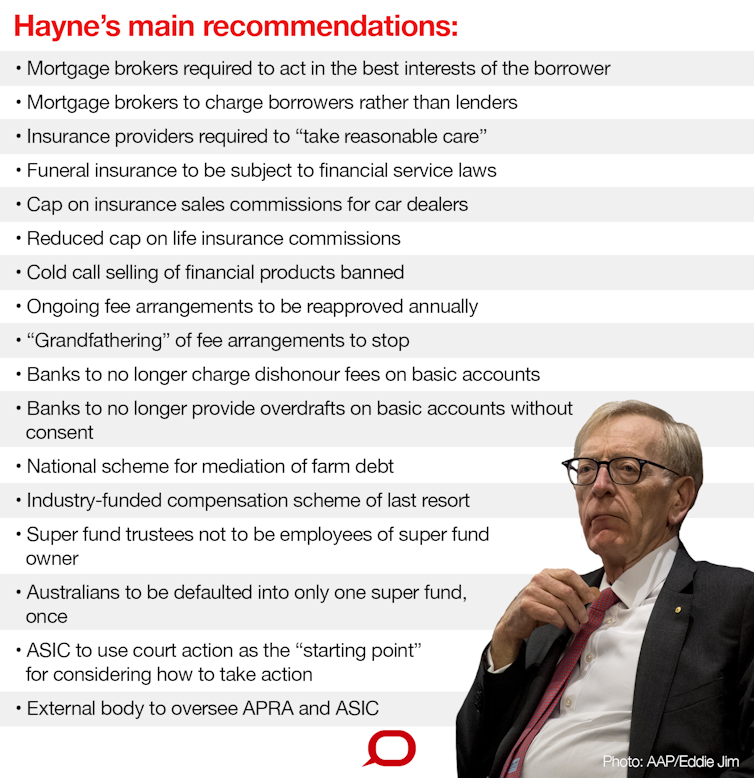

Hayne wants to simplify the law, but he says the overall task is wider.

It will require examination of how the existing law fits together and identification of the policies given effect by the law’s various provisions. Only once this detailed work is done can decisions be made about how those policies can be given better and simpler legislative effect.

Our Australian Research Council Discovery project on Rationalising the Law of Misleading Conduct[9] is undertaking precisely this task for the rules about misleading conduct, trying to track how the various laws and regulations overlap and interact with the ancient, evolving and equally complex general laws governing contracts, torts and equitable principles.

This initial “mapping” task requires sustained and expert attention, so much that it might seem beyond governments’ usual attention-spans.

But, faced with the enormity of the task, Commissioner Hayne doesn’t engage in a counsel of despair. Instead, he picks two easier steps that could be done quickly in order to make a real difference.

First, get rid of exceptions, carve-outs and qualifications. An example he uses is the special treatment given to grandfathered commissions, but carve-outs are everywhere.

Reducing their number and their area of operation is itself a large step towards simplification. Not only that, it leaves less room for “gaming” the system by forcing events or transactions into exceptional boxes not intended to contain them.

We should be clear about what is at stake. The rule of law demands that like cases must be treated alike. It follows that exceptions need to be strongly justified. And they haven’t been. Instead, exceptions and carve-outs reflect the lobbying of powerful industry groups concerned to preserve their own self-interest. And in some cases a failure on the part of the drafters to understand how the regime as a whole fits together and works.

The second step is to draw explicit connections in the legislation between the particular rules that are made and the fundamental principles to which they are intended to give effect.

Drawing that connection will have three consequences. It will explain to the regulated community (and the regulator) why the rule is there and, at the same time, reinforce the importance of the relevant fundamental norm of conduct. Not only that, drawing this explicit connection will put beyond doubt the purpose that the relevant rule is intended to achieve.

But a serious concern remains: how to do it without complicating the law further.

It might be time to take the leap and go back to basics: to reduce the legislation to the core principles and leave the detailed explanation of how they work in practice to “soft law” guidelines.

On how this might look, see our contribution Statutory interpretation and the critical role of soft law guidelines in developing a coherent law of remedies in Australia[10] in R Levy et al (eds) “New Directions for Law in Australia: Essays in Contemporary Law Reform”.

Australian Financial Complaints Authority Operational Guidelines[8]

It raises the question of why the law needs to be so complex when the alternative to it doesn’t need to be.

Simplification has to start somewhere

Hayne wants to simplify the law, but he says the overall task is wider.

It will require examination of how the existing law fits together and identification of the policies given effect by the law’s various provisions. Only once this detailed work is done can decisions be made about how those policies can be given better and simpler legislative effect.

Our Australian Research Council Discovery project on Rationalising the Law of Misleading Conduct[9] is undertaking precisely this task for the rules about misleading conduct, trying to track how the various laws and regulations overlap and interact with the ancient, evolving and equally complex general laws governing contracts, torts and equitable principles.

This initial “mapping” task requires sustained and expert attention, so much that it might seem beyond governments’ usual attention-spans.

But, faced with the enormity of the task, Commissioner Hayne doesn’t engage in a counsel of despair. Instead, he picks two easier steps that could be done quickly in order to make a real difference.

First, get rid of exceptions, carve-outs and qualifications. An example he uses is the special treatment given to grandfathered commissions, but carve-outs are everywhere.

Reducing their number and their area of operation is itself a large step towards simplification. Not only that, it leaves less room for “gaming” the system by forcing events or transactions into exceptional boxes not intended to contain them.

We should be clear about what is at stake. The rule of law demands that like cases must be treated alike. It follows that exceptions need to be strongly justified. And they haven’t been. Instead, exceptions and carve-outs reflect the lobbying of powerful industry groups concerned to preserve their own self-interest. And in some cases a failure on the part of the drafters to understand how the regime as a whole fits together and works.

The second step is to draw explicit connections in the legislation between the particular rules that are made and the fundamental principles to which they are intended to give effect.

Drawing that connection will have three consequences. It will explain to the regulated community (and the regulator) why the rule is there and, at the same time, reinforce the importance of the relevant fundamental norm of conduct. Not only that, drawing this explicit connection will put beyond doubt the purpose that the relevant rule is intended to achieve.

But a serious concern remains: how to do it without complicating the law further.

It might be time to take the leap and go back to basics: to reduce the legislation to the core principles and leave the detailed explanation of how they work in practice to “soft law” guidelines.

On how this might look, see our contribution Statutory interpretation and the critical role of soft law guidelines in developing a coherent law of remedies in Australia[10] in R Levy et al (eds) “New Directions for Law in Australia: Essays in Contemporary Law Reform”.

The Conversation

The Conversation

References

- ^ the resignation of NAB chair Ken Henry did (theconversation.com)

- ^ delay the proceeding and increase legal expenses (www.austlii.edu.au)

- ^ more than 30 pieces of state and federal legislation (financialservices.royalcommission.gov.au)

- ^ legislative porridge (www.austlii.edu.au)

- ^ Banking Code of Practice (www.ausbanking.org.au)

- ^ Financial Complaints Authority (www.afca.org.au)

- ^ fair in all the circumstances (www.afca.org.au)

- ^ Australian Financial Complaints Authority Operational Guidelines (www.afca.org.au)

- ^ Rationalising the Law of Misleading Conduct (findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au)

- ^ Statutory interpretation and the critical role of soft law guidelines in developing a coherent law of remedies in Australia (press-files.anu.edu.au)

Authors: Elise Bant, Professor of Law, University of Melbourne

Read more http://theconversation.com/understanding-hayne-why-less-is-more-110509