National accounts show past performance no guarantee of future results

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW

Wednesday’s GDP figures[1] were good. Growth was up 0.9% in the June quarter and 3.4% over the past 12 months.

As they say in baseball: “You can’t boo a home run.” But you can ask how likely the batter is to do it next time. The detail behind the figures raises further questions.

How good were they really?

Even before we get to that, it’s worth noting than GDP per capita was up 0.5% in the quarter, amounting to a 1.8% increase over the year. That’s good, but half as much as headline growth. Per capita growth is what drives living standards.

Even on an annual basis per capita growth bounces around. The following chart shows it is usually less than 2% and only occasionally reaches 3%, but never too far from zero – even excluding the GFC.

Growth per capita is volatile in no small part because immigration is volatile.

Standard economic theory tells us that in the long run immigration has very little impact on GDP per capita unless it drives a shift in the population’s mix of skills.

But in the short run it depresses GDP per capita because the fixed capital (such as buildings and machines) has to be shared between more workers.

Read more: Australia could house around 900,000 more migrants if we no longer let in tourists[2]

Since immigration is somewhat lumpy, and the skill mix is neither obvious nor constant, there can be pretty substantial swings in GDP per capita in a high-immigration economy. At 1.6% per annum, Australia’s population growth is roughly double the OECD average, so it’s best not to get too hung up on the quarterly numbers.

Good for how long?

The larger and more pressing question in whether this quarter’s good numbers will last.

There are reasons to be sceptical. First, household expenditure was a key component of the recent growth numbers. As ABS chief economist Bruce Hockman put it:

Growth in domestic demand accounts for over half the growth in GDP, and reflected strength in household expenditure.

We’ve been sustaining strong household expenditure by saving less, but that’s unlikely to continue.

In an economy in which heavily indebted households face mortgage rate hikes from two of the big four banks (most likely to be four very soon) despite no official increase in interest rates, household spending will come under pressure.

Wages growth is still languishing at around 2% (the most recent wages price index came in at 2.1%[3]), meaning that households aren’t earning much extra income.

Add to this a lower Australian dollar putting pressure on the price of imports –such as mobile phones, iPads and computers, to name a few – and it seems brave to predict continued robust consumer spending.

Special for how long?

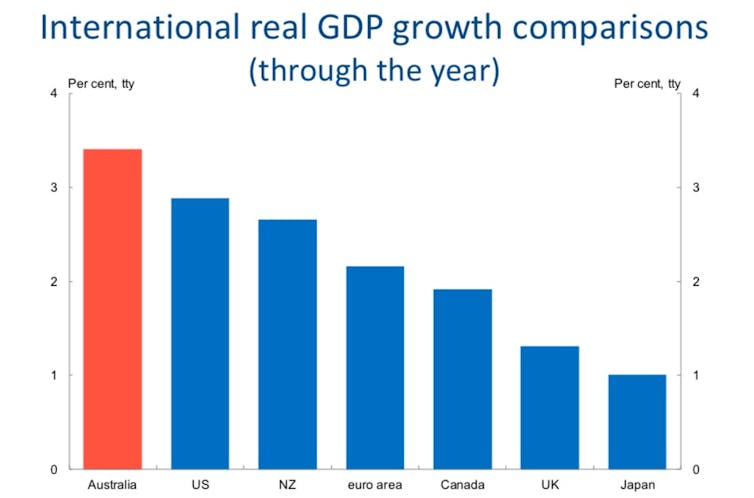

It is also worth being a bit cautious about the case for Australian exceptionalism. Yes, we’ve had a run of 27 odd years of continuous economic growth. Yes, we weathered the financial crisis better than most.

But we are also part of a global economy that is yet to see the full effects of the Trump trade war. And we are subject to the same sort of pressures that other advanced economies are facing: stubbornly low wages growth despite historically low unemployment, inflation that won’t grow, and an uncertain outlook for China – our most important trading partner.

How Australia compares.

Commonwealth Treasury

How Australia compares.

Commonwealth Treasury

Can we really return to the trend growth rates of the 1990s while the countries we compare ourselves with struggle? I hope so, but I doubt it.

The newly minted treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, couldn’t help but take credit for this week’s good news. Fair enough. But he might want to be cautious. Quarterly numbers have a habit of reversing themselves. And with an election not too far away it’s politically risky to tie oneself too closely to the vagaries of the macroeconomy in general and the forecasts of Treasury and the Reserve Bank in particular.

Reserve Bank Governor Phil Lowe might have mentioned that to Frydenberg in their much photographed recent meeting.

References

- ^ Wednesday’s GDP figures (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Australia could house around 900,000 more migrants if we no longer let in tourists (theconversation.com)

- ^ the most recent wages price index came in at 2.1% (www.abs.gov.au)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW