Australians worry more about losing jobs overseas than to robots

- Written by Nicholas Biddle, Associate Professor, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

Not a week goes by without a news story (or a few) about people losing their jobs to robots, or the potential effects of a rapidly changing labour market. We are told repeatedly about how many jobs are going to be lost. Both unskilled and skilled jobs are predicted to disappear.

These risks are no doubt real, if uncertain in their magnitude. But these prognoses are largely the work of academics and economic forecasters. How do Australians feel about their job prospects in an age of automation? Rather than robots, the 25th ANUPoll[1] finds our greatest concerns are the risks posed by poor management and jobs going overseas.

Read more: Why we don't need to prepare young people for the 'future of work'[2]

The ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods[3] with the Social Research Centre[4] recently asked a representative sample of more than 2,500 Australians about their anxieties related to the future of work. The ANUPoll[5] finds that Australians are reasonably sanguine about their current jobs. However, we are concerned about finding employment in the future if we lose our job.

Pointedly, Australians are more concerned about the threats posed by poor business management and international workers willing to work for lower wages than about the prospect of our jobs disappearing through automation. To put this another way, we are more worried about the globalisation of employment and trade than about competition from robots.

What did we ask and what did we find?

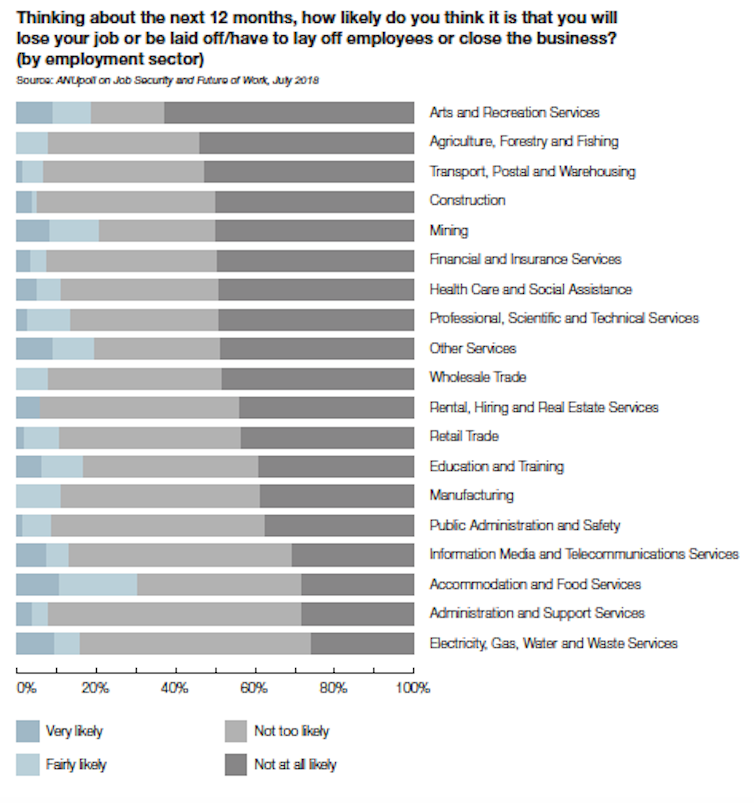

A core question in this ANUpoll is: “Thinking about the next 12 months, how likely do you think it is that you will lose your job or be laid off/have to lay off employees or close the business?”

The overwhelming majority surveyed believe it is “not at all likely” (44.9%) or “not too likely” (42.8%).

Australian workers are quite comfortable with their current job security. But the level of comfort varies by sector of employment.

Workers in the arts and recreation sector feel the most secure: 62.5% believe it’s “not at all likely” they will be laid off or need to lay off employees. At the other end of the spectrum, only 25.8% of workers in the electricity, gas, water and waste industries think it’s not at all likely.

We also asked workers: “If you were laid off how easy would it be for you to find a job with another employer with approximately the same income you now have?”

More than half – 54.6% – say finding an equivalent new job would be “not easy at all”. Only 10% believe it would be “very easy”.

Responses to this ANUPoll suggest Australian workers feel largely comfortable about their current employment but are less optimistic about their prospects should they become unemployed.

Sources of job insecurity

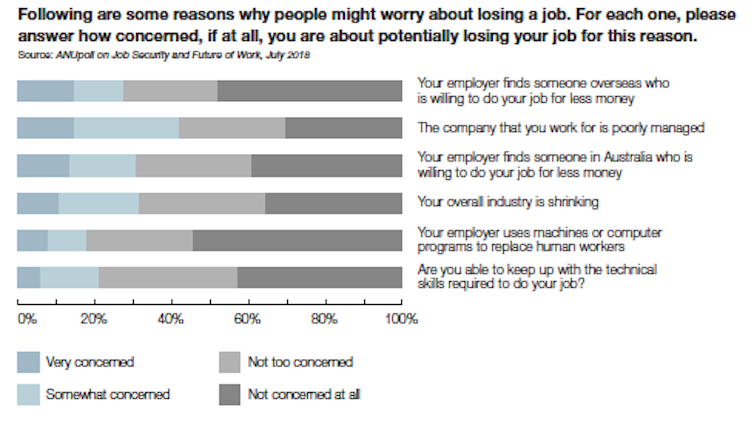

Workers may feel insecure about their employment for many reasons. We asked Australian workers about their level of concern about six different potential threats to their job.

Workers in the arts and recreation sector feel the most secure: 62.5% believe it’s “not at all likely” they will be laid off or need to lay off employees. At the other end of the spectrum, only 25.8% of workers in the electricity, gas, water and waste industries think it’s not at all likely.

We also asked workers: “If you were laid off how easy would it be for you to find a job with another employer with approximately the same income you now have?”

More than half – 54.6% – say finding an equivalent new job would be “not easy at all”. Only 10% believe it would be “very easy”.

Responses to this ANUPoll suggest Australian workers feel largely comfortable about their current employment but are less optimistic about their prospects should they become unemployed.

Sources of job insecurity

Workers may feel insecure about their employment for many reasons. We asked Australian workers about their level of concern about six different potential threats to their job.

The most common concern is that poor management of the company that employs them will lead to losing their job, with 14.7% “very concerned” by this threat and 27.6% “somewhat concerned”. This is followed by: their overall industry is shrinking; their employer might find someone else in Australia who is willing to do the job for less money; and their employer might finding someone overseas who is willing to do their job for less money.

People are least concerned that employers may use machines or computers to replace human workers. Only 8% are “very concerned” and 9.8% “somewhat concerned”.

This is followed by an inability to keep up with the technical skills needed to do their job, with 6% “very concerned” and 15.2% “somewhat concerned” about this.

Read more:

Will technology take your job? New analysis says more of us are safer than we thought, but not all[6]

Why should we be concerned about the future of work?

The labour market is no doubt changing. New occupations are being created as others become more precarious.

Occupations that rely on creativity or human-to-human interaction are both being developed and expanding their share of the labour market. Those based on routine tasks, even complicated ones, are set to employ fewer and fewer workers.

Labour markets have always adjusted to new circumstances. However, we can reasonably argue that the current transformation of work will be more comprehensive and more rapid than before. This is at least partially due to a confluence of significant trends: increased computing speed, decreased computing costs, greater network speed and capacity, increased availability of data, the lessening of some barriers to international trade, and political and economic change in countries with large skilled and semi-skilled workforces.

These changes are having political ramifications. Voters’ anxiety about the labour market and their job prospects was significant in the election of Donald Trump in the US, Brexit in the UK and the increased success of populist parties and platforms in many countries.

What to do about job security

Attention is increasingly shifting from merely describing trends in job security and the future of work to understanding the attitudes and anxieties of the current and future workforce. These attitudes will help determine the effect of labour market change (perceived and actual) on the subjective well-being of the population. Attitudes to job security and the future of work also may affect people’s receptiveness to related policy proposals.

How to respond to the public’s views on job security depends on how accurate you think those perceptions are. There are many suggested policy responses. Examples include a universal basic income and re-regulation of the labour market.

Read more:

Could the idea of a universal basic income work in Australia?[7]

If you think the perceptions identified in the recent ANUPoll are a reasonable assessment of the risks to people’s jobs, then the focus should be at least as much on outsourcing and management practices as on skills mismatch and automation. If you think the public is underestimating these latter potential threats and under-investing in the retraining and skills development that would reduce their negative consequences, then greater public attention might be justified.

The most common concern is that poor management of the company that employs them will lead to losing their job, with 14.7% “very concerned” by this threat and 27.6% “somewhat concerned”. This is followed by: their overall industry is shrinking; their employer might find someone else in Australia who is willing to do the job for less money; and their employer might finding someone overseas who is willing to do their job for less money.

People are least concerned that employers may use machines or computers to replace human workers. Only 8% are “very concerned” and 9.8% “somewhat concerned”.

This is followed by an inability to keep up with the technical skills needed to do their job, with 6% “very concerned” and 15.2% “somewhat concerned” about this.

Read more:

Will technology take your job? New analysis says more of us are safer than we thought, but not all[6]

Why should we be concerned about the future of work?

The labour market is no doubt changing. New occupations are being created as others become more precarious.

Occupations that rely on creativity or human-to-human interaction are both being developed and expanding their share of the labour market. Those based on routine tasks, even complicated ones, are set to employ fewer and fewer workers.

Labour markets have always adjusted to new circumstances. However, we can reasonably argue that the current transformation of work will be more comprehensive and more rapid than before. This is at least partially due to a confluence of significant trends: increased computing speed, decreased computing costs, greater network speed and capacity, increased availability of data, the lessening of some barriers to international trade, and political and economic change in countries with large skilled and semi-skilled workforces.

These changes are having political ramifications. Voters’ anxiety about the labour market and their job prospects was significant in the election of Donald Trump in the US, Brexit in the UK and the increased success of populist parties and platforms in many countries.

What to do about job security

Attention is increasingly shifting from merely describing trends in job security and the future of work to understanding the attitudes and anxieties of the current and future workforce. These attitudes will help determine the effect of labour market change (perceived and actual) on the subjective well-being of the population. Attitudes to job security and the future of work also may affect people’s receptiveness to related policy proposals.

How to respond to the public’s views on job security depends on how accurate you think those perceptions are. There are many suggested policy responses. Examples include a universal basic income and re-regulation of the labour market.

Read more:

Could the idea of a universal basic income work in Australia?[7]

If you think the perceptions identified in the recent ANUPoll are a reasonable assessment of the risks to people’s jobs, then the focus should be at least as much on outsourcing and management practices as on skills mismatch and automation. If you think the public is underestimating these latter potential threats and under-investing in the retraining and skills development that would reduce their negative consequences, then greater public attention might be justified.

References

- ^ 25th ANUPoll (csrm.cass.anu.edu.au)

- ^ Why we don't need to prepare young people for the 'future of work' (theconversation.com)

- ^ ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods (csrm.cass.anu.edu.au)

- ^ Social Research Centre (www.srcentre.com.au)

- ^ ANUPoll (csrm.cass.anu.edu.au)

- ^ Will technology take your job? New analysis says more of us are safer than we thought, but not all (theconversation.com)

- ^ Could the idea of a universal basic income work in Australia? (theconversation.com)

Authors: Nicholas Biddle, Associate Professor, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

Read more http://theconversation.com/australians-worry-more-about-losing-jobs-overseas-than-to-robots-100728